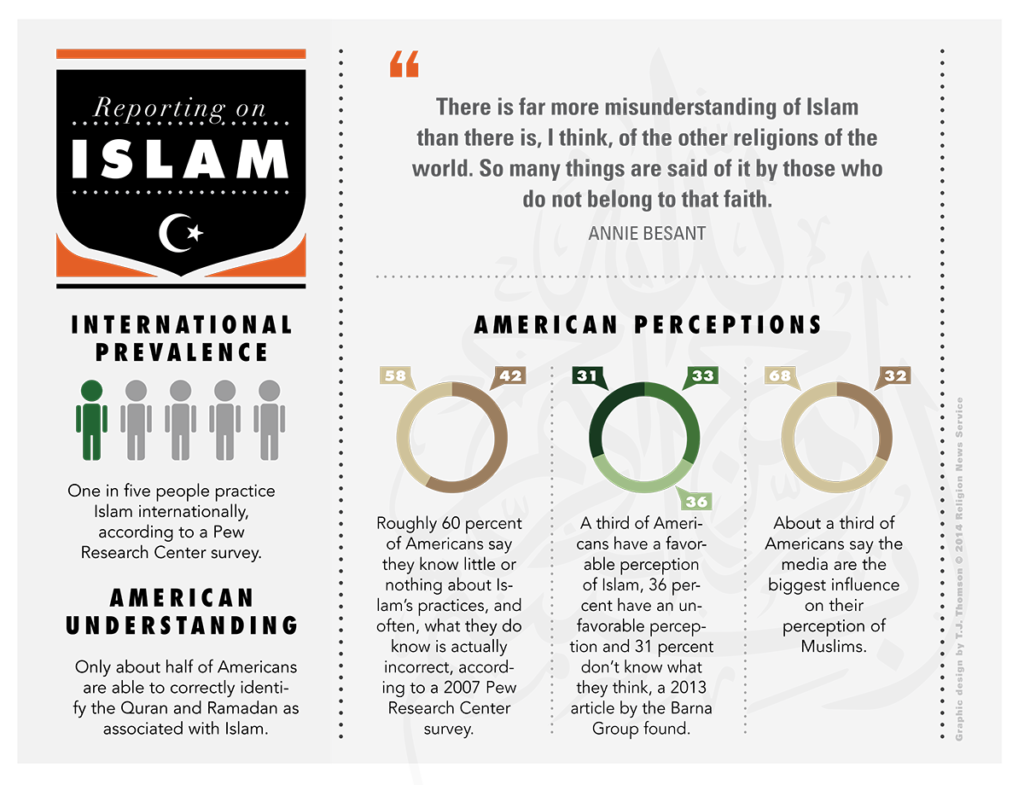

While nearly 1 in four people identify as Muslim across the globe, a Pew Research survey in 2019 found that only six-in-ten U.S. adults know that Ramadan is an Islamic holy month and that Mecca is Islam’s holiest city and a place of pilgrimage for Muslims.

Since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the U.S. Muslim population has grown and media coverage of Islam diversified, but it many U.S. adults “know little about Islam or Muslims, and views toward Muslims have become increasingly polarized along political lines” according to another Pew survey in 2021.

Meanwhile, the media remain one of the biggest influences on the perception of Muslims in the public sphere. What media communicate reflects and reinforces popular perceptions of Islam and Muslims, in turn shaping related political, legal, social, and economic decisions.

In other words, how Muslims are portrayed in the media matters. Research shows that there is a causal link between rhetoric, tone of coverage, and public perception with policy preferences, political outcomes, and potentially violent acts against minority groups.

And yet, study after study shows that over the past few decades, coverage of Muslims in U.S. (and global) media has been decidedly negative, even when compared other minority religions or ethnic groups (e.g., African Americans, Latinos, Mormons, atheists, Hindus, Jews).

Therefore, coverage of Islam and its adherents is a critical issue for journalists to consider. This guide provides reporters, commentators and analysts with background information on Islam and a brief guide to covering Muslims, with a specific focus on the U.S.

Background

The world of Islam

Islam is the second-largest religion in the world. Muslim majority countries extend from North Africa to Southeast Asia and there are minority populations across the world, from Chile to Chechnya, New Zealand to Newfoundland.

Islam is also associated with two other monotheistic religions — Muslims, Jews and Christians all believe in one God, whom Muslims refer to as Allah (“the God”). Muslims believe that Allah revealed the Quran to his chosen messenger, the Prophet Muhammad, in the form of the Quran. The word “Islam” is derived from the Arabic root s-l-m, which means “submission” or “peace.” The word “Muslim” is usually translated as “those who submit” or “those who surrender” to Allah and his will for humanity.

It is estimated that there are at least 1.6 billion Muslims throughout the world. Though the Middle East and North Africa are most often associated with Islam, the majority of Muslims reside in Africa and Asia, with some of the largest Muslim communities found in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Central Asia, and Nigeria. In other words, and although they are often mistakenly conflated, not all Muslims are Arabs (anyone with Arabic as a native language), nor are all Arabs Muslims. Arab Muslims make up only 15 percent of the world’s total Muslim population. Of the world’s 220 million Arabs, about 10 percent are non-Muslims. There are significant non-Muslim populations (Christian, Jewish, Yazidi, etc.) among Arab populations. Indonesia is the largest Muslim nation, with 237 million Muslims (86.7 percent of its populace). Throughout the world however, Muslims strive to learn Arabic so they can read, recite, and understand the Quran as well as perform ritual prayers.

In the U.S., no racial or ethnic group makes up a majority of Muslim adults. About three-in-ten are Asian (28%), including those from South Asia, and one-fifth are black (20%), according to Pew Research Center. A smaller number are Hispanic (8%), and an additional 3% identify with another race or with multiple races.

Covering Islam, covering Muslims

In his 1981 book Covering Islam, Palestinian author Edward Said critiques the hidden agendas and misrepresentations that often underlie even the most “objective” coverage of Islam and Muslims in the Western media. Said critiqued how in its coverage of events such as the Iranian Revolution, the U.S. news media have portrayed “Islam” as a singular community “synonymous with terrorism and religious hysteria.”

In more recent, and empirical, research, Erik Bleich and A. Maurits van der Veen echo Said’s cultural critique and provide quantitative analysis to show how coverage and portrayals of Islam and Muslims in the Western media remain largely negative, despite Said’s admonition for media to help dispel “the myths and stereotypes” around Islam, Muslims, the Middle East, and Asia.

While there is a spectrum of coverage on Islam and Muslims in U.S. media, the overall tone of coverage is extremely negative. Furthermore, Bleich and Maurits van der Veen argue that articles set in a foreign location or that broach topics related to violence, extremism or values clashes tend to be more negative than others.

This means that reporters should approach these topics with the utmost care and, even before they begin, question whether the topic itself will set the tone for interpretation.

The guide below helps parse out some of the nuance often missing in negative coverage of Islam and Muslims, providing insight into common questions, addressing particular issues (e.g., dress, women in Islam, and shariah) and offering some tips and tools for covering Islam and Muslims with more balance, accuracy and insight.

A brief history of Islam

In 6th Century CE (Common Era) Arabia, Islam rose to prominence amid a melting pot of religious beliefs and political pressures. Interactions between the Christian Byzantine Empire, the Persian Sassanid Empire, the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia, pagan Arabian tribes and Jewish communities influenced the geopolitics of Arabia and the larger Middle East on the eve of Islam’s appearance.

Islam’s Prophet, Muhammad, was born in Mecca (located in modern-day Saudi Arabia) in 570 CE. During Ramadan (which occurs in the Islamic calendar’s ninth month), Muslims believe that Muhammad experienced a revelation from Allah while meditating in a nearby cave, where the Angel Gabriel appeared to him with a message.

Muhammad soon began to share his revelation with family and friends. Over time, he spread the message publicly, preaching the monotheistic message “God is One” and bidding people to surrender to Allah in belief and practice.

In an era of internicene warfare, Muhammad’s message of peace was met with opposition. Muhammad fled to the nearby city of Medina, about 250 miles north of Mecca, in 622. This event came to be known as the Hijrah (emigration) and marked the beginning of the Islamic era and calendar (signified by AH, or “after Hijrah”).

Eventually, despite a period of great conflict, Muhammad was able to unite warring tribes and triumphantly return to Mecca in 629 (7 AH). He died in Medina in 632 (10 AH) with no male heir, leading to political divisions within the Muslim community (ummah). By the time of his death, most of Arabia had converted to Islam.

During Europe’s Middle Ages, Islamic civilizations thrived in what has been called their “Golden Age.” Well before the European Renaissance, a “Muslim Renaissance” in math, science, and philosophy consolidated Greek, Persian, Indian and Chinese wisdom into a potent package that benefitted centuries of European development in the centuries that followed. Gunpowder, the compass and advanced sails all entered Europe via Muslims. Moreover, Greek classics from Aristotle, Plato, Pythagoras, Ptolemy, Euclid, and Hippocrates were reintroduced to the world through houses of learning sponsored by Muslim benefactors, which rendered these works into Arabic.

As a result, words such as algebra, alcohol, alchemy, guitar, chemistry, zero, nadir, coffee, cotton, rice, atlas, camel, and so forth came from Arabic into European languages. For example, modern Spanish contains some three thousand words of Arabic origin.

When Mongol invaders destroyed the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, Baghdad, in 1258, more than 36 public libraries were already in existence. In the same year, the Ottoman Empire rose to prominence under the leadership of the Turk, Osman Ghazi, who was born in 1258. After Baghdad fell to the Mongols, the Seljuk Turks declared an independent Sultanate in east and central Asia Minor. Osman died in 1326, after having laid the foundation for the Ottoman empire, which that lasted for 600 years — until the end of World War I.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, however, many Islamic nations, societies, and empires — including the Ottomans in the early 20th — fell to European imperial powers before beginning the process of renewal and revival in the 20th century and beyond. Beginning in the 18th and 19th centuries, Muslims also spread throughout the world via a series of economic, political, and social migrations.

Additional background and historical context on Islam can be found via the following resources:

- Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World through Islamic Eyes, by Tamim Ansary

- The Story of the Qur’an: Its History and Place in Muslim Life, by Ingrid Mattson

- The Caliph and the Imam, by Toby Matthiesen

- Lost Islamic History: Reclaiming Muslim Civilisation from the Past, by Firas Alkhateeb

- The Crusades through Arab Eyes, by Amin Maalouf

- The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition: A Compendium of Knowledge from the Classical Islamic World, by Elias Muhanna

- The History of Islam in Africa, edited by Nehemia Levtzion and Randall L. Pouwels

- The Muslims of Latin America and the Caribbean, by Ken Chitwood

- “Islam In America: From African Slaves to Malcolm X,” by Thomas Tweed

Background & groups

Over time, the Muslim community has splintered into different branches. Reporters should be sensitive to the varying beliefs of these branches, as the Muslim community is not a monolithic entity. There are many different groups and factions under the umbrella of Islam. Those seeking general information about Islam must take care to note which community they are speaking to and where they lie on the spectrum between mainstream and marginalized. As with other religious traditions, different sects interpret Islamic teachings in different ways that can be regarded as classical or traditional, modern or reformist.

The word “fundamentalist” should not be used in reference to Muslim groups. Technically, all Muslims turn to the fundamentals of their religion, since they abide by the teachings of the Quran and Muhammad (the Sunnah), but the addition of the term overlooks this context and often adds only pejorative meaning. Furthermore, not all groups termed “Muslim” are considered as such by other Muslims (e.g., the Ahmadiyya).

Here is a quick breakdown of some of the most prominent communities, sects, movements, and branches of Islam worldwide:

Sunnis: The Sunnis make up 80-90 percent of the global Muslim population. Their name is derived from the Sunnah, or the example of the life of Muhammad, which forms the core of Sunni teaching. All Muslims are guided by the Sunnah, but Sunnis stress it as the core of their jurisprudence, alongside other sources like the Quran, ijma (consensus), and qiyas (analogy). Sunni Muslims also ascribe to six articles of faith, known as the pillars of iman. These are:

- Reality of one God (Allah)

- Existence of Allah’s angels

- Authority of the books of Allah

- Following the prophets of Allah

- Preparation for and belief in the Day of Judgment

- Supremacy of Allah’s will

Sunni life is guided by four schools of legal thought: Hanafi, Maliki, Shafii and Hanbali.

Sunni Islam generally lacks a formalized hierarchy, though that may differ depending on setting, locale and culture. For example, most mosque communities select their own imam to lead Friday prayer services.

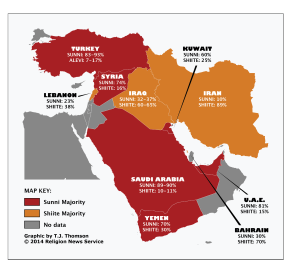

Shiites: The Shiites make up the majority of the remaining 10-20 percent of the world’s Muslim population, constituting the majority of the population in places like Iran, Azerbaijan, Bahrain and Iraq. Shiism developed after the death of Muhammad, when his followers split over who would lead Islam. Shiism favored Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali Ibn Abi Talib, believing that divine guidance was passed on to the Prophet’s descendants. Its followers are called Shiites (or “the followers” or “party of Ali”).

There are three main branches of Shiites today: the Zaydis, the Ismailis (or “Seveners”), and the Ithna Asharis (or “Twelvers” or “Imamis”). The Zaydis (followers of Zayd ibn Ali ibn al-Husayn [695–740 CE]) are found in Yemen, Iraq, and parts of sub-saharan Africa. Ismailis are a branch of the Shiites led by the Aga Khan, the hereditary title given to the branch’s leader. They are predominantly an Indo-Iranian community, but can also be found in India, Pakistan, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, China, Jordan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East Africa and South Africa. In recent years, they have also emigrated to North America, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. The Ithna Asharis form the largest contingent of Shiites worldwide. They believe there are twelve imams, beginning with Ali and ending with Muhammad al-Mahdi, who they believe went into hiding (occultation) and will return at the end of time as the messianic imam to restore justice, equity and peace.

Ibadis: An early school of thought that is neither Sunni nor Shiite, dominant in Oman and throughout many parts of Africa. They are considered a moderate offshoot from the Kharijis, who seceded from both Sunni and Shii camps in the contest over Islamic leadership following the Prophet’s death. There are only one million adherents worldwide and they have a high regard for the authority of their imam and teachers (ulama).

Sufis: This is Islamic mysticism, often understood to be the internalization or intensification of Islamic practice and belief. Not a separate sect per se, Sufis can be found among both Sunnis and Shiites.

Known for poetry by writers such as the 13th-century Persian writer Rumi, Sufism often involves worshipful dancing, music and the methodical repetition of divine names (dhikr). It is more a type of practice of Islam than a standalone denomination. Some Muslims are critical of Sufism as an unjustified innovation (bid’a).

Wahhabis: Founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (a Hanbali scholar), this is an 18th century reform movement within Islam, which became dominant in Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Wahabbis (or Muwahhidun) follow a literal interpretation of the Quran and strict allegiance to the notion of tawhid (the oneness and unity of Allah). They advocate for a sociomoral restructuring of society according to their interpretation of Islamic law.

Most people in the West knew nothing of Wahhabism until after the 9/11 attacks, which were organized by Osama bin Laden, a professed Wahhabi. Wahhabism has spread rapidly since the 1970s, when the oil-rich Saudi royal family began contributing money to it.

Salafis: The Salafi movement has been often described as closely linked to or synonymous with the Wahhabi movement; however, Salafists consider the term “Wahhabi” derogatory, according to French author Olivier Roy. The name Salafi is derived from the term salaf (“pious ancestor” or “predecessor”), referring to the first generations of Muslims. Modernist and intellectual, Salafism has spread across the globe as a form of traditionalist reform within Islam.

Ahmadiyya: A controversial messianic movement founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in Punjab (then, British-controlled India) in 1889. Rejected as heretical by the majority of Muslims because they believe their leader is a “non-legislative prophet,” they are widely persecuted in Muslim-majority countries (including Pakistan and India). They are very active in places like the United Kingdom, Canada, and the U.S., distributing literature, founding mosques, and conducting humanitarian aid and missionary services. There are two factions within the Ahmadiyya movement: Qadiani and Lahori, the latter emphasizing Ghulam Ahmad as a reformer and not a prophet.

Islamic schools of thought

There are four primary schools of Sunni Islamic thought and three within Shiism, each named after the imam who developed it:

Sunni

- Hanbali: Orthodox, dominant in Saudi Arabia, used by the Taliban, relies primarily on the Quran and Sunnah

- Maliki: Used in North Africa, emphasizes personal freedom

- Shafi’i: Prevalent in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Yemen

- Hanafi: Most liberal, used in Central Asia, Egypt, Pakistan, India, China, Turkey, the Balkans and the Caucasus

Shiite

- Ja’fari: Used in Iran, emphasizes hadiths that match the Quran and sunnah

- Zaydi: Only practiced in Yemen, formerly dominant in northern Iran, scholarship is known to be pluralistic and philosophical

- Isma’ili: Predominantly Indo-Iranian, but can also be found in India, Pakistan, Syria, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, China, Jordan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East Africa and South Africa (see above)

Sunni and Shiite Split

Referred to as “Islam’s foundational conflict,” what began as a political disagreement later devolved into a sectarian split defined by social, spiritual, and intellectual differences. This has created numerous forms of conflict between Sunnis and Shiites across nearly 1,400 years. Weapons development in Iran and diplomacy issues in Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, Palestine, Indonesia, Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabi, Syria and Bahrain also have fostered violence between these groups.

Both Sunnis and Shiites – drawing their faith and practice from the Qur’an and the life of the Prophet Muhammad – agree on most of the fundamentals of Islam. The differences are related more to historical events, ideological heritage and issues of leadership.

The first and central difference emerged after the death of Prophet Muhammad in A.D. 632. The issue was who would be the caliph – the “deputy of God” – in the absence of the prophet. While the majority sided with Abu Bakr, one of the prophet’s closest companions, a minority opted for his son-in-law and cousin – Ali. This group held that Ali was appointed by the prophet to be the political and spiritual leader of the fledgling Muslim community.

Subsequently, those Muslims who put their faith in Abu Bakr came to be called Sunni (“those who follow the Sunna,” the sayings, deeds and traditions of the Prophet Muhammad) and those who trusted in Ali came to be known as Shiite (a contraction of “Shiat Ali,” meaning “partisans of Ali”).

Abu Bakr became the first caliph and Ali became the fourth caliph. However, Ali’s leadership was challenged by Aisha, the prophet’s wife and daughter of Abu Bakr. Aisha and Ali went to battle against each other near Basra, Iraq in the Battle of the Camel in A.D. 656. Aisha was defeated, but the roots of division were deepened. Subsequently, Mu’awiya, the Muslim governor of Damascus, also went to battle against Ali, further exacerbating the divisions in the community.

In the years that followed, Mu’awiya assumed the caliphate and founded the Ummayad Dynasty (A.D 670-750). Ali’s youngest son, Hussein – born of Fatima, the prophet’s daughter – led a group of partisans in Kufa, Iraq against Mu’awiya’s son Yazid. For the Shiites, this battle, known as the Battle of Karbala, holds enormous historical and religious significance.

Hussein was killed and his forces defeated. For the Shia community, Hussein became a martyr. The day of the battle is commemorated every year on the Day of Ashura. Held on the tenth day of Muharram in the Islamic lunar calendar, scores of pilgrims visit Hussein’s shrine in Karbala and many Shiite communities participate in symbolic acts of flagellation and suffering.

Over time, Islam continued to expand and develop into evermore complex and overlapping societies that spanned from Europe to sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa to Asia. This development demanded more codified forms of religious and political leadership.

Sunnis and Shiites adopted different approaches to these issues.

Sunni Muslims trusted the secular leadership of the caliphs during the Ummayad (based in Damascus from A.D. 660-750) and Abbasid (based in Iraq from 750-1258 and in Cairo from 1261-1517) periods. Their theological foundations came from the four religious schools of Islamic jurisprudence that emerged over the seventh and eighth centuries.

To this day, these schools help Sunni Muslims decide on issues such as worship, criminal law, gender and family, banking and finance, and even bioethical and environmental concerns.

On the other hand, Shiites relied on Imams as their spiritual leaders, whom they believed to be divinely appointed leaders from among the prophet’s family. Shiite Muslims continue to maintain that the prophet’s family are the sole genuine leaders. In the absence of the leadership of direct descendants, Shiites appoint representatives to rule in their place.

Other disputes that continue to exacerbate the divide include issues of theology, practice and geopolitics.

For example, when it comes to theology Sunnis and Shiites draw from different “Hadith” traditions. Hadith are the reports of the words and deeds of the prophet and considered an authoritative source of revelation, second only to the Quran. They provide a biographical sketch of the prophet, context to Quranic verses, and are used by Muslims in the application of Islamic law to daily life. Shiites favor those that come from the prophet’s family and closest associates, while Sunnis cast a broader net for Hadith that includes a wide array of the prophet’s companions.

Shiites and Sunnis differ over prayer as well. All Sunni Muslims believe they are required to pray five times a day, but Shiites can condense those into three.

Example coverage

“Differences masked during Hajj” – August 1, 2017, The Conversation

During the Hajj – the pilgrimage to Mecca, held annually and obligatory for all Muslims once in a lifetime – it may seem that these differences are masked, as both Sunnis and Shias gather in the holy city for rituals that reenact the holiest narratives of their faith. And yet, with Saudi authorities overseeing the Hajj, there have been tensions with Shia governments such as Iran over claims of discrimination.

And when it comes to leadership, the Shia have a more hierarchical structure of political and religious authority invested in formally trained clergy whose religious authority is transnational. There is no such structure in Sunni Islam.

The greatest splits today, however, come down to politics. Although the majority of Sunni and Shia are able to live peacefully together, the current global political landscape has brought polarization and sectarianism to new levels. Shia-Sunni conflicts are raging in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Pakistan and the divide is growing deeper across the Muslim world.

This historical schism continues to permeate the daily lives of Muslims around the world.

Storylines to Consider

When it comes to covering Islam and Muslims, there are numerous angles to take — and key issues that will be explored in further detail below — but what are some storylines that journalists might consider in their coverage of Islam? How might our coverage become less stigmatized and hyper-focused on violence, extremism, and values clashes? Here is a critical, if not exhaustive, list of several ideas you might pursue in your coverage:

- American Muslim Diversity – There is no one profile that you can use to describe Muslims in the U.S. American Muslims are a diverse community, with adaptable and wide-ranging views on political, social, and religious issues. According to a Pew Research Center report in 2017, “No racial or ethnic group makes up a majority” of the nearly 3.5 million Muslim Americans. Among the largest subsets of the community are immigrants from the Middle East and South Asia, with smaller shares of Black and Hispanic Muslims. Beyond race and ethnicity, Muslims in the U.S. are marked by considerable diversity when it comes to their religious beliefs and practice, political perspectives, and opinions on a range of social questions. Reporters would do well to highlight this diversity in their coverage. In particular, covering Muslims “on the margins” — both in the U.S. and abroad — can help elicit different kinds of stories than the media is used to covering.

- Read “American Muslims Are A Diverse Group With Changing Views,” from Five Thirty Eight.

- Muslim Finance and Philanthropy – One of the areas where you see less reporting on Islam and Muslims is in regards to money. Not only are there a range of regulations and rituals related to the broad topic of “Islamic finance” — the provision of financial services in accordance with Islamic law, principles and rules — worth reporting on, there are also numerous stories waiting to be told when it comes to Muslim philanthropy and contributions to American civil society. According to research by the Muslim Philanthropy Initiative at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, “Muslims give more towards both faith-based causes and non-faith-based causes than non-Muslims” in the general U.S. population. How might your reporting further explore the ways in which Muslims are using their money and avoid stereotypes about financing terror?

-

- Read “How Muslim Americans meet their charitable obligations: 3 findings from new research,” from The Conversation.

- Muslims in the Media – Beyond coverage of Muslims by the media, what about Muslims in media. Stories about Muslim actors, producers, writers, celebrities, comedians, influencers, musicians, and yes, journalists, have increased in recent years. Still, there is much left to report as more Muslim Americans populate television, theater, and digital screens. In particular, how are Muslims being represented in shows and films? Has there been a significant shift in public opinion as Muslims emerge as significant content creators? What are the opportunities and limitations of increased representation?

-

- Read “Mo Amer on Growing Up as a Muslim Refugee in Houston,” from Texas Monthly.

- Immigration – Stories on Muslim migrants and newcomers are nothing new. Your coverage, however, could take reporting on the topic in a new direction. To get beyond the usual stories about demographic change, the fear of extremism, and value clashes, consider the stories of individual Muslim migrants — their journeys, their motivations for moving, and their experience in the U.S. Do not be afraid to go beyond the Islamophobia angle either. A story about Muslim migrants does not have to be negative. It can be a well-reported, critical but compassionate take on the Muslim migrant experience. This issue is all the more important, as was noted above, because the vast majority of Muslims in the U.S. are immigrants or have an immigrant background.

-

- Read “African and Invisible: New York’s Other Migrant Crisis,” from The New York Times.

- Interreligious Dialogue – Muslims have long been involved in interreligious dialogue, but there has been a renewed effort in recent years by leaders, clerics, and public figures to play a larger and more intentional role as part of multi-religious efforts at peace building. From the grassroots to the regional, national, and inter-governmental level, more and more Muslims are not only engaged in interreligious efforts, they are often leading the way. Think of Eboo Patel of Interfaith America, Azza Karam of Religions for Peace International, the National Catholic Muslim Dialogue (NCMD) — a joint venture between the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), and the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA) — or the Saudi-backed International Dialogue Center (KAICIID) in Portugal. Each organization listed above, though not without some controversy, has featured Muslim support and leadership. How might your reporting reflect these efforts on the ground in your context?

-

- Read “Eboo Patel Is Leading Interfaith America Into The New Era Of Religious Diversity,” from Religion Unplugged.

- Read “Eboo Patel Is Leading Interfaith America Into The New Era Of Religious Diversity,” from Religion Unplugged.

- Holidays and the Islamic Calendar – Islamic holidays are a great “hook” to do some of the deeper reporting that Islam and Muslims in the U.S. — and around the world — need in Western media sources. Reporters can also provide helpful “explainers” on how the Islamic calendar functions in the lives of Muslims. Beyond Ramadan (the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, in which fasting is required), there are two major, canonical festivals (or Eids) marking the end of Ramadan and the end of annual pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj). But, some Muslims also celebrate Muhammad’s birthday (Mawlid an-Nabi), Ashura, (a day of commemoration), and other local commemorations or nights of remembrance from the life of the prophet or Islamic history. A great place to start would be to familiarize yourself with the Islamic calendar and its holidays as well as reach out to local Muslims in your area about their celebrations across the year.

-

- Read “How this Islamic holiday became uniquely Caribbean,” from The Conversation.

- Family Dynamics and Life Cycles — There is an exoticism and tendency to focus on headline grabbing news when it comes to covering Islam and Muslims. But what about everyday life? The vast majority of U.S. readership would have very little appreciation for the daily, and banal, aspects of Muslim life and experience. How might your reporting help shine a respectful, but revealing, light on Muslim marriage and family life, daily rituals and household dynamics, or significant rites of passage and life cycle customs? There has been excellent reporting on these topics in more recent years, talking about aqeeqah ceremonies (sacrifice and/or cutting a child’s hair at seven days old), what it is like to be a Muslim teen in the U.S., and Islamic burial ritual adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic or in American urban contexts in general.

-

- Read “After life: Muslim deathcare in New Haven,” from Yale Daily News.

- Arts and Education — In their extensive analysis of media coverage of Islam and Muslims in Western media, Erik Bleich and A. Maurits van der Veen found that stories on the arts and education were both the least common and the least negative of all the stories in their data set. Therefore, when considering how journalists might help shift the generally negative tone of most media coverage on Islam and Muslims, they suggested more stories on such themes. How might you or your publication ramp up coverage on Muslim artists or benefactors? What about the expanding Islamic education infrastructure in the U.S.? What about Muslim fashion designers and university professors studying topics we might not expect? How might your coverage of these issues avoid stigmatization and instead contribute to a broader, and deeper, appreciation for Islam and Muslim life?

-

- Read “These Muslim artists are reenvisioning the prayer rug,” from Artsy.

What is Shariah?

Shariah means “the way,” traditionally in reference to a path to a source of sustenance, such as a watering hole (sometimes the difference between life and death in a desert environment).

Not a strict or set-in-stone body of law, shariah is better understood as Allah’s will for humanity, an immutable set of wide-ranging moral principles and examples drawn from the Quran and the practices and sayings (Sunnah) of Prophet Muhammad.

These broad ethical principles and practices are then interpreted and applied by jurists to come up with specific legal rulings and moral prescriptions. These human efforts to codify Islamic ethical norms are widely referred to as Islamic law, or fiqh in Arabic. While fallible and open to interpretation, revision, and contextual adaptation, the term shariah is still sometimes used to refer to the entirety of Islamic legislation.

“What Shariah means: 5 questions answered” – June 16, 2017, The Conversation

I want to caution against reducing Sharia to just one or two legal principles and picking out certain punishments as being characteristic of Sharia. It is much more fruitful to start with Sharia’s fundamental objectives.

Sharia provides guidance on how to live an ethical life. It lays down guidelines on how to pray and how to treat one’s family members, neighbors and those who are in need. It requires Muslims to be just and fair in their dealings with everyone, to refrain from lying and gossip, etc., and always to promote what is good and prevent what is wrong.

Muslim scholars reflecting on the larger objectives of Sharia have said that laws derived from it must always protect the following: life, intellect, family, property and the honor of human beings. These five objectives create what we may consider to be a premodern Islamic Bill of Rights, providing protection for civil liberties.

On the specific question of adultery, Islam, like some other religions, takes a strong position, since it seeks to promote the sanctity and stability of the family. Those found guilty of adultery are supposed to be punished by lashing (based on the Quran) or stoning (based on hadith).

But there is a high bar of evidence that must be met before this punishment can be meted out: Four witnesses must observe the actual act of penetration. Even in this age of voyeurism, it would be next to impossible to meet this criterion. The prescribed punishment for adultery was therefore hardly ever carried out in the premodern world.

This situation is in contrast to the brutal stonings that have been carried out in the modern, post-colonial period in a handful of Muslim majority countries, like Nigeria and Pakistan. From my perspective, the above-mentioned rules of evidence were not given due regard. In many such cases, modern jurists who may have very little training in classical Islamic law and do not understand the principles of Sharia are being asked to implement “Islamic punishments” by politicians who want to appear Islamic. Stoning appears to be a dramatic way of asserting a shallow “Islamic” identity, often in conscious opposition to the West. There are other jurists who have criticized these sensationalist examples of stoning as being in violation of fundamental moral and legal principles within Islam. — Read more.

Belief systems, cultural customs, and state authority

It is important for non-Muslims to navigate the tensions between Islamic beliefs and patriarchal customs operating within communities, nations, and regions. Iran, for instance, is a state where freedom is at odds with authority. This often results in unequal treatment of women, such as difficult divorces and forced veiling (where men do not have the same difficulty or expectations in terms of dress code).

Under the majority of interpretations of Islamic law, women have the right to own property, pursue education and participate fully in social and political life. Many Muslim jurists also point out that Islamic law does not categorically forbid women to drive; that the Quran forbids a bride price; and the Quran does not mention female genital mutilation, which is practiced in northern regions of Africa and in parts of North America and Europe. Such issues need to be carefully, and painstakingly, reported, with an awareness that there is no single “Islamic law” and that interpretations of shariah vary across different historical, political, ethnic, and geographic contexts.

Abortion is another contentious issue that has recently stirred debate. Different schools of thought have different time restrictions in terms of acceptable abortions, even as the Quran does not explicitly discuss abortion. “Sanctity of Life: Islamic Teachings on Abortion” explains that abortion is generally forbidden by the religion, but is acceptable if having the baby will put the mother’s life in danger. But, as scholar explains, “there is no single Islamic attitude about abortion.”

Example coverage

“There is no one Islamic interpretation on ethics of abortion, but the belief in God’s mercy and compassion is a crucial part of any consideration” – July 8, 2022, The Conversation

Islam isn’t monolithic, and there is no single Islamic attitude about abortion. The answer to the question depends on what kinds of Islamic sources, scriptural, legal or ethical, are applied to this contemporary issue by people of varying levels of authority, expertise or religious observance.

Muslims have had a long-standing, rich relationship with science, and specifically, the practice of medicine. This has yielded multiple interpretations of right and wrong when it comes to the body, including ideas about and practices surrounding pregnancy. — Read more.

Issues to be aware of

Journalists in predominately non-Muslim contexts should be aware that Islamic practices in regard to diet, money and other matters of daily life may differ from majority practices or that which is considered “normal” according to general Judeo-Christian standards in places like the U.S. or Europe.

Besides being treated skeptically according to a general invalidation of religion in Western contexts, some Muslim practices may generate tension or confusion. Journalists should treat such topics with care, keeping in mind how their coverage will often impact how Muslims and non-Muslims interact around such issues.

These practices include:

- Friday prayers – Muslims gather at mosques for congregational prayers on Fridays at the midday prayer time, but unlike Christians observance on Sunday or Jewish Shabbat on Saturday, the entire day is not considered a sabbath. Often, Friday is considered the weekend in Muslim-majority contexts, but that is far from universal.

- Diet – Muslims are not permitted to consume pork or alcohol and require meat and poultry to be slaughtered and prepared according to certain standards (halal). Muslims cannot consume animal shortening, lard, gelatin or any product containing alcohol (for example, Dijon mustard). The American Halal Foundation has a good description of how to follow Muslim dietary laws.

- Dogs — Often considered impure and unclean in many traditional Islamic communities. There is a hadith that mandates ritual washing before prayer for anyone who comes in contact with a dog’s saliva. At the same time, the Quran speaks favorably about dogs and grants permission (even praising as good) food that is caught by a trained hunting dog.

- Holidays – Muslims follow a lunar calendar, which is 11 days shorter than the Gregorian calendar. That means that the dates of holidays shift on the January to December calendar, and holidays begin at sundown, with the sighting of the new moon.

- Money and finance – Islamic law bans collecting or paying interest, so Muslims use alternate ways to pay for large purchases, such as cars, homes and insurance. Financial institutions in non-Muslim countries are increasingly aware of the principles and practices of Islamic finance. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), even provides an overview of recent developments and best practices.

- Fasting during Ramadan — As explained in more detail below, Ramadan is a month of fasting, prayer and reflection for Muslims. It is a time when practicing Muslims refrain from food, drink, smoking and sex from sunrise to sunset. In Muslim-majority countries, the entire calendar and pace of daily life shifts to accommodate the practice. In non-Muslim countries, where this is not the case, some Muslims may struggle to fast. Many are starting to seek accommodations from their employers. Civil rights laws provide a number of protections to ensure that no one suffers workplace discrimination because of their religious beliefs, including “reasonable accommodation” to employees for religious practices such as prayer or fasting.

- The Prophet — Protests in Europe over cartoon images of Muhammad showed how seriously Muslims take a general ban on visual images of the Prophet and other human/animal figures. Most Muslims consider this an act of idolatry. However, as is evidenced in the story below, the issue of Muhammad’s portrayal requires a nuanced approach.

- Dress — This issue will be dealt with in more detail below, but take note that because modesty is a highly prized virtue in Islam, expectations about dress and grooming are emphasized for both men and women. Non-Muslims, however, often interpret these customs and distinctions between how Muslim men and women dress as gender inequality.

Example coverage

“Why the Media Didn’t Publish the Muhammad Paintings at the Heart of the Hamline Controversy” — May 5, 2019, VOA

”The practice of fasting in Muslim nations is presumably much more common during Ramadan, since there are likely to be more practicing Muslims,” says Hassan. “And fasting is a part of the daily culture during this month. Thus, if people you know are fasting, you’re likely to do the same.”

Most Muslim countries also make it easier for people to fast. Across the Middle East, Ramadan must be observed in public. Which means, even non-Muslims must refrain from eating, drinking and smoking in public. In most of these countries, religious police patrol the streets and violators are usually punished. Most cafes, restaurants and clubs are closed during the day although some hotels serve food in screened-in areas or through room service.

Most public offices and schools are closed and private businesses are encouraged to cut back their hours to accommodate the fasters.

“Being part of an environment or community where fasting is encouraged and accommodated can increase the likelihood of people fasting successfully,” Hassan says. “In some Muslim countries, accommodations are provided for fasting, which may not always be the case in the West” or in other non-Muslim nations.

“Observing Ramadan as a minority has its challenges. But it is not significant enough to make it impossible to fast,” says Naeem Baig of the Islamic Circle of North America. He says it is made easier because “people from other faiths generally are respectful and supportive towards their Muslim colleagues or neighbors.”

Making accommodations

Mansouri, in India, will have to accommodate her fasting while spending weekdays at her job as a teacher in a Hindu school. She says she will try to keep herself busy so as not to think of food when teachers and children take their lunch break.

Similarly, Baig says, “We encourage Muslim parents to inform the schools their children attend and let the teachers know that their children will not be going for lunch break. In most public schools, Muslim children of fasting age can go to the library during lunch and are exempt from PE (physical education).” — Read more.

Dress

Keeping in mind Islam’s general emphasis on modesty in dress and intersex interactions (see above), what else might journalists better understand as they cover Muslims and explore issues related to gendered sartorial practices?

First, it is important to note that “hijab” not only refers to a head covering, but is a general term to describe modest dress. Both Muslim men and women observe hijab, the Quran’s requirement that one dress modestly, and both loose, nontransparent clothing is emphasized for both genders. It can include a headscarf, or a veil that partially covers the face; a burqa, which covers the face and body; or a chador, which is a cloak that covers the body. It can also include a jilbab worn to cover everything except the head and hands in public. Help the reader understand what it is and be specific about what it is that is being called a hijab.

Depending on how they interpret the instructions for women, some Muslim women wear garments that cover their heads or their whole bodies. Some women do not cover their heads and simply wear clothes that are modest. As a journalist, it is best to ask, rather than assume.

Debates on dress

Efforts to ban veiling practices in the West are also an issue relevant to coverage of Islam, indicated by support of banning full veiling in Western European countries. Several European states have introduced full or partial bans of the burqa, including: Austria, France, Belgium, Denmark, Bulgaria, the Netherlands (in public schools, hospitals and on public transport), Germany (partial bans in some states), Italy (in some localities), Spain (in some localities of Catalonia), Russia (in the Stavropol Krai), Luxembourg, Switzerland, Norway (in nurseries, public schools and universities), and Kosovo (in public schools), Bosnia and Herzegovina (in courts and other legal institutions).

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the public does not support banning, according to Pew Research. In fact, there are numerous examples of non-Muslims donning hijab in what they position as an act of solidarity with “gendered Islamophobia.”

Reporters must be careful to understand, however, that some Muslim women wear hijabs, or head scarves, while others do not. In some cultures, women cover their entire bodies by choice. There have also been debates over dress beyond veiling. For example, there is a campaign for modest dress in Qatar and UAE targeted at expatriates. Both men (wear the kandura) and women (wear the abaya) typically wear full cloaklike coverings in these regions. This shows that covering veiling and dress in regards is an important issue in terms of personal freedom versus authority in different countries.

At the very least, reporters should endeavor to understand “the way hijab functions for the Muslim women who wear it, and the values associated with it” according to religious studies scholar Liz Bucar, before reporting on the issue or questions related to it.

Example coverage

“In ‘Stealing My Religion,’ Liz Bucar takes on murky forms of appropriation” — November 18, 2022 Religion News Service

Progressives and liberals donned hijabs to be in solidarity with Muslim women and combat gendered Islamophobia, but they did it in a way that really centered themselves, and that enforced white secular feminism. Some Muslim woman felt like it was another layer of being othered and tokenized and decentered and erased.

The act erases half the Muslim women in the U.S. who don’t wear a hijab. I also think if people really understood the way hijab functions for the Muslim women who wear it, and the values associated with it, they would see why it might not be appropriate as a form of political protest and solidarity. There’s something really odd about taking a religious practice which is about humility and modesty, and then putting it on your head and taking a selfie or posting on social media to get a lot of likes and to virtue signal that you are against gendered Islamophobia. Part of the dynamic with solidarity hijab was a lot of white non-Muslim women centering themselves as the true feminists, rather than following and learning from others.

The liberal political agenda of fighting gendered Islamophobia, which is a good thing, didn’t take the time to be truly intersectional in its approach to the problem. They didn’t actually ask the community what it wanted, and sometimes what the community wants is harder to give. — Read more.

Women in Islam

Many misconceptions persist about the role of women in Islam. Contrary to these perceptions, the original teachings of the Quran were controversial at the time because of their high regard for women, treating them as an integral part of Arab society. However, the steady accretion of patriarchal authority throughout history has meant women have — as with other societies, polities, and cultural systems — been marginalized and mistreated.

Nonetheless, because Muslim life largely revolves around the family, Muslim women command great respect in all their roles, especially as mothers.

Women are spiritually and intellectually equal to men under Islamic law. Although the rights of Muslim women vary by country, most Muslim nations afford women rights with regard to marriage, divorce, civil rights, legal status, inheritance, education and clothing.

Even so, there are legal and social restrictions placed on women within an Islamic legal framework, many of which have been codified into state law in some Muslim-majority nations like Malaysia, Pakistan, or Saudi Arabia. Since the 19th-century, numerous male and female scholars have spoken out about the status of women and published works advocating for reform in education, politics, and various spheres of public life. Debates continue over the level of female participation in the public realm, even as numerous Muslim women have taken up significant cultural, political, economic, and religious roles.

A 2011 study by Pew Research, “Muslim Americans: No Signs of Growth in Alienation or Support for Extremism,” indicated that roughly half of U.S. Muslims support gender separation during prayer at a mosque.

But some Muslims who call themselves “progressive” are urging that women should be allowed to lead prayers or sit with men during prayers. There is also debate on separation in other countries. Numerous female-led or women’s only mosques have sprung up in places like South Africa, the U.S., Canada, or the Maldives in recent years.

Participation also occurs outside the mosque. Muslim women participate in sporting events, including sports like car racing, boxing or soccer.

“Donning a Headscarf in the Cockpit” profiles a Muslim woman in Tehran who is the star of car racing. Another article, “An Inspiration to Young Women around the World,” explores the growing number of Muslim women who play sports and excel.

Example coverage

“American Muslim women are finding a unique religious space at a women-only mosque in Los Angeles” — April 30, 2022, The Conversation

The Women’s Mosque of America was founded in 2015 by two South Asian American Muslim women – comedy writer M. Hasna Maznavi and attorney Sana Muttalib. It was conceived as a space to empower Muslim women to take on active roles in their individual community mosques and influence changes in a mosque culture that is often unwelcoming to women.

The mosque hosts monthly Friday prayers where women exclusively run the services. One woman calls the adhan, or call to prayer, while another delivers the sermon and leads the all-female congregation in prayer. Yet, as I explore in my forthcoming book, the mosque’s contribution to creating a different kind of Muslim community is not simply its placement of women in leadership roles, but rather the way it elevates particular issues as worthy of concern in religious communities.

For example, with women at the helm of this mosque, the sermons focus on connecting Islamic scriptures to women’s lived experiences in both their personal and professional lives.

Topics have ranged from sexual violence, divorce and motherhood to social justice activism and support for the Black Lives Matter movement. As I learned in my interviews with community members, congregants are eager to hear these types of sermons, which they see as missing in their traditional mosque communities. — Read more.

Domestic violence

Writing about American Muslim efforts against domestic violence, religion scholar Juliane Hammer commented that abuse is often made invisible in public discourse. Though it occasionally becomes big news through exceptional cases or campaigns to raise awareness, domestic abuse can often go unreported or unnoticed.

Even so, there is a stunning amount of quantitative and qualitative research on the prevalence and dynamics of domestic violence in the U.S., including its root causes and ruinous effects. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence:

- Nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner in the United States, equating to more than 10 million women and men annually.

- Based on reported cases, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 9 men have experienced severe intimate partner physical violence and 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner, including slapping, shoving and pushing, which in some cases might not be considered “domestic violence.”

- About 4,000 women die each year due to domestic abuse.

- From that total, 75% of the victims were killed attempting to leave the relationship or after the relationship ended.

There are no data to show how many victims and survivors are religious or if their abuse was directly related to religion. However, the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence reported that across traditions, “issues of religious faith, or the belief in a specific system of principles and practices that give reverence to a higher power, are often central to the experiences of many victims and survivors of domestic violence.”

Muslim activists in the U.S. figure that approximately 10% of Muslim women are abused emotionally, psychologically and/or physically by their husbands.

Example coverage

“Explainer: what Islam actually says about domestic violence” — June 12, 2017, The Conversation

Islam’s position on domestic violence is drawn from the Qur’an, prophetic practice (sunnah), and historical and contemporary legal verdicts (fatwas).

The Qur’an and prophetic practice clearly illustrate the relationship between spouses. The Qur’an says the relationship is based on tranquillity, unconditional love, tenderness, protection, encouragement, peace, kindness, comfort, justice and mercy.

The Muslim prophet, Muhammad, set direct examples of these ideals of a marital relationship in his personal life. There is no clearer prophetic saying about a husband’s responsibility toward his wife than his responsewhen asked:

Give her food when you take food, clothe her when you clothe yourself, do not revile her face, and do not beat her.

Muhammad further stressed the importance of kindness toward women in his farewell pilgrimage. He equated the violation of their marital rights to a breach of the couple’s covenant with God.

Abusive behaviour towards a woman is also forbidden because it contradicts the objectives of Islamic jurisprudence – specifically the preservation of life and reason, and the Qur’anic injunctions of righteousness and kind treatment.

Domestic violence is addressed under the concept of harm (darar) in Islamic law. It includes a husband’s failure to provide obligatory financial support (nafaqa) for his wife, a long absence of the husband from home, the husband’s inability to fulfil his wife’s sexual needs, or any mistreatment of the wife’s family members. — Read More.

Core beliefs

The five pillars

Islam has Five Pillars of practice, which are required of all Muslims.

1) The Shahada, or declaration of faith: A Muslim must express his or her faith by declaring in Arabic, “There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.” This declaration expresses that the purpose of life is to serve Allah alone, and it must be recited, understood and enacted in faith by all Muslims in their daily life.

2) Salat, or prayer: Muslims are required to pray five daily prayers in order to attain peace and harmony. Mental concentration, verbal communication, vocal recitation and physical movement are all components of this prayer. An hour-long special congregational prayer is also delivered on Friday at noon in the mosque. Ritual cleanliness is essential, and prayer can be performed anywhere.

3) Support almsgiving: Islam teaches that it is a sin not to share one’s wealth with the needy or to allow others to suffer while personally prospering. Each year, Muslims make a payment to charity, which is based in amount on a percentage of their income or property. This is called zakat, which means both “purification” and “growth.”

4) Sawm, or fasting: Islam follows a lunar calendar. During Ramadan, the ninth month in the lunar calendar, all Muslims above the age of maturity (14 or 15) fast, or abstain from eating, drinking and engaging in sexual activity with spouses during the hours between dawn and sunset. The sick, pregnant women, nursing mothers, women who are menstruating and people traveling are all excused from fasting; however, they are required to feed a needy person one meal each day or make up for lost days later. Fasting serves the purpose of instilling patience and self-control, helping the individual resist temptations and show obedience to Allah.

5) The hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca: Mecca, known as the Ka’bah, is the center of the Muslim world, and a powerful symbol of Muslim unity and the sole worship of Allah. Once in a lifetime, depending on health and material means, all Muslims are required to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. This journey is the hajj.

More than 2 million Muslims from all over the world congregate in Mecca each year for the hajj. Simple white garments are worn to emphasize equality before Allah without discrimination based on of race, color, language or nationality. The close of the hajj is marked by the festival of Eid al-Adha.

Example coverage

“A peek into the lives of Puerto Rican Muslims and what Ramadan means post Hurricane Maria” — May 17, 2018, The Conversation

For Juan, Ramadan is a balancing act. On the one hand is his religious faith and practice. On the other is his land, his culture, his home: Puerto Rico.

Although he weaves these two elements of his identity together in many ways, during Ramadan, the borderline between them becomes palpable. For the Puerto Rican Muslims like Juan, the holy month of fasting brings to the surface the tensions they feel in their daily life as minorities – and as Muslims among their Puerto Rican family and Puerto Ricans in the Muslim community.

That is even more true this year in the wake of Hurricane Maria, the storm that made landfall in the southeastern city of Yabucoa on Sept. 20, 2017, and devastated parts of Puerto Rico. Even today, many parts of the island are without essential services, such as consistent electricity and water or access to schools.

I met Juan in 2015, when I first traveled to Puerto Rico in an effort to better understand the Puerto Rican Muslim story as part of my broader research on Islam in Latin America and the Caribbean. What I have found, in talking to Muslims in Puerto Rico and in many U.S. cities, is a deep history and a rich narrative that expands the understanding of what it means to be Muslim on the one hand, and, on the other, Puerto Rican. This Ramadan, Muslims in Puerto Rico are using the strength of both these identities to deal with the havoc of Hurricane Maria. — Read more.

Scripture

Allah and the Quran

Muslims do not worship Muhammad (only Allah), but they believe he was chosen by Allah to be the final prophet for his message of peace. This message of peace is Islam, recorded in Arabic in the 114 chapters (or surahs) of the Quran or al-Quran in Arabic, meaning “The Recitation.” Muslims consider it to be a precise transcription of Allah’s words to Muhammad through the Archangel Gabriel over a 23-year period. It is read and recited in accordance with a set of rules and regulations meant for proper reception and sonic encounter.

Read! In the name of your Lord who created: He created man from a clinging form. Read! Your Lord is the Most Beautiful One who taught by the pend” (Quran 96: 1-4)

Thought the Quran is the foundational text for Islamic jurisprudence, only 500 of its 6,236 verses are cited or consulted in the process of developing instructions for how to live Islamically. For Muslims, the Quran is more than a holy book or scripture for reference, it is an experience with the divine and a means of understanding the world through Allah’s voice. After a series of controversies in the early centuries of Islam’s development, the majority of Muslims believe the Quran is — in some ways similar to the Christian doctrine of incarnation — an articulation of God present in the world.

As such, the Quran embodies the importance of peace – internal peace, peace and submission to Allah, peace with other people and peace with the world as a whole.

When writing, be aware that other transliterations of “Quran” exist, such as Koran or Qu’ran; however, the Associated Press recommends “Quran” as the preferred spelling, unless a specific group or individual requests an alternate spelling.

- Islamic-Dictionary.com: Islamic-Dictionary.com provides the meaning, traditional Arabic form, and pronunciation of Islamic words.

- “The Koran”: Read the full electronic text of the Koran, posted by University of Michigan and translated by M.H. Shakir. The site allows users to search Koran through key words, chapters and phrases.

Hadiths

In addition to the Quran, Muslims also rely on thousands of hadith, reports of the words and deeds of the Prophet Muhammad and his companions. These are also considered an authoritative source of revelation, though there are debates about the reliability and authority given to particular collections. The most famous and authoritative of the collections include those by al-Bukhari and Muslim among Sunni and al-Kulayni and al-Tusi among Shiites.

Pluralism

Muslims trace their roots to the Prophet Adam and believe in all of the prophets celebrated by Jews and Christians. They consider Jesus a prophet; however, they do not consider him divine. Muslims consider the followers of Judaism and Christianity fellow People of the Book (Ahl Al Kitab), and they respect the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, though believe that they have been corrupted over time.

Some scholars point to the “constitution of Medina” as a unique example of “pluralistic theocracy” within Islamic tradition, wherein Muhammad and the early Muslim community acknowledged in their midst the people of the Ahl Al Kitab. This acknowledgement, however, is not coterminant with the secular understanding of pluralism: it was hierarchical, with limited/little recognition for the space of non-monotheistic religions within the nascent Islamic community.

Still, across time and space, Islam has had lengthy encounters with other religion traditions like Hinduism and Buddhism, given that two-thirds of Muslims live in South and Southeast Asia. The concept of Ahl al-Kitab, and the related ahl al-Dhimma, has therefore been extended to include other groups besides those mentioned.

Today, numerous Muslim organizations, leaders, and institutions are involved in a variety of pluralistic endeavors and agreements, ranging from the Amman Message of 2009 calling for tolerance and unity to an agreement between the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA) and Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), an Indonesian Islamic association that claims 90 million members worldwide.

Not all Muslim endeavors at interreligious engagement and dialogue have been welcomed, however, as the controversy around the International Dialogue Center (KAICIID), funded significantly by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (but founded with support from the Republic of Austria, the Kingdom of Spain and the Holy See as a founding observer) forced them to relocate their headquarters from Vienna, Austria to Lisbon, Portugal in 2022.

Example coverage

“Religions for Peace made history with its new leader. Then came historic challenges.” — October 5, 2021, Religion News Service

In August of 2019, Azza Karam became the first woman and first Muslim to be appointed secretary-general of Religions for Peace, replacing William Vendley, who had led the international interfaith organization and worked for peace across Africa and Asia for more than half of the group’s 49-year history.

Her historic appointment would not be a topic of conversation for long. Within a few months of her taking over, the world was in the grips of the coronavirus pandemic and the staggering death toll and global recession it sparked. This year, the U.S. pullout of Afghanistan brought on political chaos in that country, with ripples around the world. — Read more.

Celebrations

In the world of Islam, there are two major celebrations, Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha. Eid literally means a “festival” or “feast” in Arabic. Because the Muslim calendar operates on a lunar cycle, the dates of these events vary annually on the Gregorian calendar.

Ramadan is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar and commemorates the time during which the faithful believe Allah sent the Angel Gabriel to Muhammad in Mecca and gave him the teachings of the Quran.

The beginning of Ramadan is determined by whether a new moon is sighted. As such, it is not always possible for Muslim leaders to predict the exact dates in advance. Most months in the Islamic calendar have 29–30 days. The first day of the month is marked by the sighting of the hilal (crescent moon). Weather conditions can delay moon sightings and thus influence when a new month starts.

Two proper greetings during Ramadan are “Ramadan Mubarak” or “Salaam,” which means “peace” and can be used at any time. Participating Muslims observe Ramadan by abstaining from eating, drinking and sexual relations from dawn to sunset during a 29- or 30-day period.

Eid al-Fitr marks the end of the Ramadan and is a joyous three-day celebration. Often, relatives and friends exchange good tidings and a special Eid prayer is said. Children receive gifts, and sweets are enjoyed.

In many countries with large Muslim populations, it is a national holiday. Schools, offices and businesses are closed so family, friends and neighbors can enjoy the celebrations together. Saudi Arabia has announced a 16-day holiday this year for Eid. In Turkey and in places that were once part of the Ottoman-Turkish empire such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Azerbaijan and the Caucasus, it is also known as the, “Lesser Bayram” (meaning “lesser festival” in Turkish).

Eid al-Adha is a three-day celebration that generally falls about 2½ months after Eid al-Fitr. The greater of the two events, Eid al-Adha celebrates the end of the hajj, or the pilgrimage to Mecca. All Muslims take part whether they participated in the pilgrimage that year or not. The purpose of Eid al-Adha is to spend time with family, give thanks and commemorate Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Ismail for Allah. In the spirit of this sacrifice, many Muslims sacrifice their own livestock and share the meat with family, friends and the needy. Eid al-Adha is also known as the “Greater Bayram.”

Example coverage

“Stamford schools add only one holiday — Eid al-Fitr — to calendar after months of debate.” — January 26, 2023, Stamford Advocate

After weeks of discussions about the calendar for next school year — which featured holidays taken off then put back on and new ones being added — only one change was ultimately adopted Tuesday night.

The Muslim holiday Eid al-Fitr […] will be a day off of school for the 2023-24 school year. The holiday had never been included in Stamford’s school calendar in the past.

The Stamford Board of Education approved the calendar during a meeting Tuesday night, but not after making some adjustments to a proposal that was before them.

That proposal also included Three Kings Day, Diwali, and Eid al-Adha as additional new holidays, even though all three fall on weekends during the upcoming school year. Board president Jackie Heftman made a motion to place all three in a note at the bottom of the calendar to acknowledge them, but not as days off from school.

“The perception out there that people are feeling is that once it goes on the calendar even if it is a weekend, the following year when it isn’t a weekend, it would be a school holiday,” she said. — Read more.

Notes on coverage

Terminology and labels

- Muslim refers to people. Islam refers to the faith, and the adjective form is “Islamic.”

- Avoid labeling extremist or terrorists groups as Islamic, even if they describe themselves as such. If the term is necessary to the story, seek out balance and diverse Muslim opinions. Use additional caution for headlines.

- There is no easy way to characterize the differences between the two main branches of Islam, Sunni and Shiite, so reporters should be careful not to make generalizations.

- The Nation of Islam is an organization of predominately Black Muslims led by Louis Farrakhan. It is not considered a mainstream Islamic group. The Nation of Islam was founded by Elijah Muhammad in 1930. When Elijah Muhammad died in 1975, his son W. Deen Muhammad took over and began moving the organization toward mainstream Sunni Islam. He eventually changed its name to the American Society of Muslims. Farrakhan disagreed with this new direction and restarted the Nation of Islam in the early 1980s. While he has moderated its views somewhat, the Nation of Islam, based in Chicago, is still associated with intolerant views toward some groups.

- Islam is very diverse, and there are many misconceptions about who is Muslim. Many Arabs are Muslims, but many are not. In addition, many Muslims are not Arab, including the growing number of Black Muslims and Muslim converts (although Muslims often say people “revert” to Islam instead of “converting” to it). Some U.S. mosques are dominated by Muslims from a particular country or region, but many mosques draw worshippers from dozens of countries.

Take caution with the following terms:

- Allah: This specific term for “God” might make it seem that Muslims worship a specific or exclusive God. In reality, Allah is just the Arabic word for God and is used by Christian and Jewish Arabs to describe God as well.

- American Muslims: This term defines the group by religion, rather than nationality, ethnicity or race. Using “American Muslim” might frame Muslim individuals in the U.S. as having more allegiance to Muslim countries or Islam itself over the United States government and culture.

- Fatwa: A fatwa is a legal ruling delivered by an Islamic legal authority in response to a question posed by an individual or legal body. Even though this is a non-binding opinion or judgment, many Westerners view fatwas as official, and sometimes harsh, judgments.

- Islamic terrorism: This term should be avoided in coverage because it suggests that there is a tie between terrorist acts and Islam or that terrorism follows Islamic values.

- Islamists/Islamism: This term is often used as a blanket term for a variety of groups, both violent and nonviolent, from political parties to terrorist organizations. Most often, the term should be used to describe institutions or individuals seeking the application of Islamic values in political arenas.

- Islamofascism: This is problematic because it links fascism and Islam, which are actually in opposition.

- Jihad/jihadists: The use of these words should be watched carefully as Muslims and non-Muslims or Westerners might have different meanings connected to them. While Muslims see jihad as an inner struggle to be closer to God, jihad is linked to terrorism and violent acts in Western media.

- Liberal democracy: Journalists should be careful here because labeling a government as such might make it sound like the government is accepting, or victim to, Western values.

- Moderate Muslim/Islam: While this term suggests secular influence and anti-extremism, journalists should hesitate using it. It characterizes Islam as an opposing identity that is extreme or violent.

- Secularism/secular society: When writing about different nation-states, journalists should not jump to define a given region as a secular society. Many Muslims see the need for religion to play a role in government and/or society, so it can be offensive to define a state as secular. The use of such discourse can also ignite negativity and tension with the “West.”

- Shariah: Shariah might be perceived as archaic and not able to adapt to modern life, which can offend Muslims. It also does not refer to a singular body of law (see above).

- War on Terror: This could be misinterpreted as “War on Islam” and readers can become confused about who the enemy in the war actually is.

About visiting a mosque

Mosque FAQ

- What are the major sections of the mosque?

- Entrance (where shoes are removed)

- Musallah (prayer room)

- Qiblah (where the imam faces in prayer)

- Mihrab (niche that shows direction of Mecca)

- Wadu facilities (place to wash hands, face and feet before prayer)

- In some mosques, there may be separate entrances for men and women.

- Who officiates services?

- The muazzin calls individuals to prayer. The imam leads prayer and gives sermons.

- What are guests expected to do at a service?

- Guests can just sit and observe or can choose to participate in the service.

- What kinds of equipment can be used in a mosque service?

- Taking pictures, using flash and using a video camera are generally not allowed. Sometimes using this equipment is OK for use if approved by a given mosque or Islamic center. Tape recorders are more likely to be approved for use.

- What happens after the service?

Religious activities and appropriate behavior in the mosque

- Journalists should take care to remove shoes and dress conservatively upon entering a mosque. Men should wear slacks and a casual shirt. Women should cover arms and legs and bring a head scarf. Open-toed shoes and modest jewelry are OK for women. Avoid wearing clothes with photographs or images of faces. Wearing visible crosses, Stars of David, zodiac signs or pendants with faces or animals is frowned upon.

- It is sometimes considered inappropriate for a stranger to shake hands with a member of the opposite sex.

- When taking photographs of Muslims at prayer, do not film or photograph them from behind. Ask permission to film from the front or from any other vantage point in the mosque.

- Avoid luncheon meetings during Ramadan, when Muslims fast from dawn to dusk. Also, many Muslims follow dietary laws, which prohibit eating pork, its byproducts, blood and the flesh of animals that died without being ritually slaughtered.

General issues

- Do not enhance racial profiling by simply running photographs and images of Muslims who, because of the way they dress, fit the stereotype.

- Do not seek out the Muslim community only when there is a crisis or major problem and a reaction is required.

- There is no one Muslim leader that can speak for all of Islam. Additionally, there is no worldwide leader of Islam, or even the major branches of the religion. Imams and other local leaders serve different functions from most pastors and rabbis and often focus most of their work on interpreting Islamic law. Because there is no central authority, theological and legal interpretations can vary by region, country or even from mosque to mosque.

- Do not rely on non-Muslims for information about Islam.

Example Coverage

“Muslim scholars tell Islamic State: You don’t understand Islam” Sept. 24, 2014, Religion News Service

More than 120 Muslim scholars from around the world joined an open letter to the “fighters and followers” of the Islamic State, denouncing them as un-Islamic by using the most Islamic of terms.

Relying heavily on the Quran, the 18-page letter released Wednesday (Sept. 24) picks apart the extremist ideology of the militants who have left a wake of brutal death and destruction in their bid to establish a transnational Islamic state in Iraq and Syria.

Even translated into English, the letter will still sound alien to most Americans, said Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council of American-Islamic Relations, who released it in Washington with 10 other American Muslim religious and civil rights leaders.

“The letter is written in Arabic. It is using heavy classical religious texts and classical religious scholars that ISIS has used to mobilize young people to join its forces,” said Awad, using one of the acronyms for the group. “This letter is not meant for a liberal audience.”

Even mainstream Muslims, he said, may find it difficult to understand.

Awad said its aim is to offer a comprehensive Islamic refutation, “point-by-point,” to the philosophy of the Islamic State and the violence it has perpetrated. The letter’s authors include well-known religious and scholarly figures in the Muslim world, including Sheikh Shawqi Allam, the grand mufti of Egypt, and Sheikh Muhammad Ahmad Hussein, the mufti of Jerusalem and All Palestine.

A translated 24-point summary of the letter includes the following: “It is forbidden in Islam to torture”; “It is forbidden in Islam to attribute evil acts to God”; and “It is forbidden in Islam to declare people non-Muslims until he (or she) openly declares disbelief.”

This is not the first time Muslim leaders have joined to condemn the Islamic State. The chairman of the Central Council of Muslims in Germany, Aiman Mazyek, for example, last week told the nation’s Muslims that they should speak out against the “terrorist and murderers” who fight for the Islamic State and who have dragged Islam “through the mud.”

But the Muslim leaders who endorsed Wednesday’s letter called it an unprecedented refutation of the Islamic State ideology from a collaboration of religious scholars. It is addressed to the group’s self-anointed leader, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, and “the fighters and followers of the self-declared ‘Islamic State.’”

But the words “Islamic State” are in quotes, and the Muslim leaders who released the letter asked people to stop using the term, arguing that it plays into the group’s unfounded logic that it is protecting Muslim lands from non-Muslims and is resurrecting the caliphate — a state governed by a Muslim leader that once controlled vast swaths of the Middle East.

“Please stop calling them the ‘Islamic State,’ because they are not a state and they are not a religion,” said Ahmed Bedier, a Muslim and the president of United Voices of America, a nonprofit that encourages minority groups to engage in civic life.

President Obama has made a similar point, referring to the Islamic State by one of its acronyms — “the group known as ISIL” — in his speech to the United Nations earlier Wednesday. In that speech, Obama also disconnected the group from Islam.

Enumerating its atrocities — the mass rape of women, the gunning down of children, the starvation of religious minorities — Obama concluded: “No God condones this terror.”

International sources

Global

-

Islamic Finder

Islamic Finder is a web tool that enables users to search for mosques by ZIP code or city.

-