One challenge in writing about the Eastern Orthodox is the debate over numbers. A figure often cited is 3 million adherents in the U.S., with about 2 million in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, 1 million in the Orthodox Church in America, and some tens of thousands in the other 20 major Eastern Orthodox churches.

In a summary posted by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, Alexey D. Krindatch of the Patriarch Athenagoras Orthodox Institute notes that the Orthodox churches in the United States have been facing several challenges since the 1970s.

These include the tug between assimilation and maintaining ethnic distinctiveness, incorporation of the increasing numbers of American-born members and of converts from inter-Christian marriages, and grassroots movements that want to see greater unity among the Orthodox communities.

This guide provides journalists with background information on Orthodox Christianity and a brief guide to covering Orthodox Christianity in American and international contexts.

Background

Overview

Eastern Orthodox churches are rooted in the earliest days of Christianity and do not recognize papal authority over their governance. During the Great Schism of 1054, the churches split from those in the western half of the Roman Empire, when those western churches recognized the supremacy of the bishop of Rome above all other bishops.

Today Eastern Orthodox churches are organized mostly around national lines and recognize the patriarch of Constantinople as their leader. The churches have 250 million to 300 million members worldwide and include the Greek Orthodox Church and Russian Orthodox Church.

In the United States the largest of these churches is the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, followed by the Orthodox Church in America, which includes followers of Bulgarian, Romanian, Russian and Syrian descent.

Branches & Groups

Orthodox Christian churches are rooted in the Middle East or Eastern Europe but do not recognize the pope as their leader. The Orthodox Church split with the Roman Catholic Church in the Great Schism of 1054, largely over issues of papal authority.

The pope in Rome claimed supremacy over the four Eastern patriarchs, while the Eastern patriarchs claimed equality with the pope. Today the spiritual head of Orthodoxy is the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, who has no governing authority over the other patriarchs but is called “first among equals.”

The Orthodox Eucharistic service is called the Divine Liturgy, and worship is very sensual, involving incense, chants and the veneration of icons. The Eastern Orthodox Christian churches include the Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem and the Orthodox Churches of America, Russia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Cyprus, Greece, Poland, Albania, the Czech and Slovak Republics, Finland, Japan, Mount Sinai and China.

Ethnicity in the Church

It is sometimes understood that Eastern Christian Church-goers are perceived as strangers to Americans. This may occur because high priority is given to preserving ethnic identity and heritage of members.

This preservation practice occurs because often the mother country language is used, children attend parochial schools instead of American public schools, and nationwide Orthodox ethnic women and youth organizations are created for attendance by specific audiences. These institutions and practices foster an ethnicity specific or generally “ethnic” identity for the group.

One resulting phenomenon of these institutions includes self-isolated ethnic communities. In comparison to Protestant and Roman Catholic traditions, Orthodoxy is defined as a more exclusive religious organization. For instance, Orthodox members sometimes frown upon “inter-Christian marriage,” or Orthodox-Not-Orthodox marriage (i.e. a Protestant and Orthodox marriage).

Example coverage

“Iraqi Christians find refuge in ancient monastery” — June 17, 2014, Jane Arraf, Al Jazeera

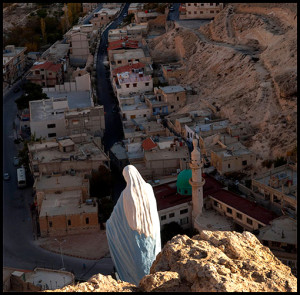

Perched on the side of a mountain surrounded by caves, St. Matthew’s Monastery has been a place of refuge since the fourth century. Some of the earliest Christians sought safety here. With the fall of the city of Mosul, just 20 miles away, the monastery’s thick stone walls have again become a sanctuary.

Along the courtyards in rooms normally used by religious pilgrims and monks, dozens of Christian families fleeing Mosul have settled in – laying out mattresses and the few belongings they carried with them. Released from school, children climb dizzying heights to play on the rocks nearby – their home city visible in the distance. Inside, their worried parents drink tea and watch news of a region that has again become a battlefront. — Read more.

Orthodox bishops chafe at Christian persecution in the Middle East

By David Steinmetz, Religion News Service

Nov. 14, 2013

(RNS) On July 25, a delegation of leaders from 15 Eastern Orthodox churches (including the U.S.) met in Moscow with Russian President Vladimir Putin to discuss the increased persecution of Christians in the Middle East.

Occasional persecution was always a hazard for Christians living as minorities in Muslim countries. Still, there were places in the Middle East where a reasonably tranquil life was possible. This was particularly true of Egypt and Syria, where Christians made up more than 10 percent of the population and often prospered as a group — urban, well-educated, and professional.

With the civil war in Syria and the civil conflict in Egypt, the instances of violent repression increased. This rise in the rate of violence signaled a change that was particularly worrying for Orthodox bishops, who lead the largest body of Christians in the Middle East.

Ironically, the Orthodox delegates from around the world did not go to Moscow to discuss the Middle East. In fact, they had been invited to Moscow by Patriarch Kirill, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, to take part in a celebration commemorating the conversion of the Russian people to Christianity more than a thousand years ago. Nevertheless, the delegates found they were compelled to talk with their Russian hosts about such events as the burning of more than 40 churches in Egypt, the random murder and drive-by killing of Christian laity in Cairo, and the kidnapping of senior clergy in Syria.

Unfortunately, the list of innocent sufferers in a civil war is very long and the losses endured by them runs very deep. Nevertheless, argued the Orthodox leaders, civil disorder in the Middle East cannot be allowed to continue. Innocent suffering must be brought to a quick end. The bishops were convinced, however, that there was no solution to the violence against either Muslims or Christians that does not begin with an immediate cease-fire and the start of intense negotiations by all the warring parties.

It is hard to imagine Orthodox bishops talking to Joseph Stalin or even Nikita Khrushchev about the plight of innocent Muslims and Christians caught in a bloody conflict they did not start and could not end. But Putin, in spite of his KGB background, has embraced the Russian Orthodox Church. What exactly is involved in that decision is a matter of debate. It is at least clear that Putin thinks that Orthodoxy adds a dimension of depth to the Russian character missing from what he regards as the superficial character of the American people. On the whole, Putin has a low view of American society (with the exception of Harley-Davidson motorcycles, which he adores).

Putin is therefore comfortable, as the old Communist hierarchy would never have been, sitting in the Kremlin palace, chatting with the patriarch of Moscow about the pastoral concerns of Orthodoxy in the Middle East. Such a friendly meeting between Putin and the leaders of Orthodoxy should not go unnoticed, certainly not in the Middle East, where Russia has interests to protect. The Orthodox bishops for their part were aware that Putin had no easy remedy for ending the violent upheavals in Egypt and Syria, but nevertheless urged him to encourage peaceful negotiations whenever he could.

Apparently Putin agreed with his visitors that some negotiation in the Middle East was still possible. In August he sold a reluctant President Obama on a Russian negotiated plan to dispose of Syria’s chemical weapons. It was not a comprehensive solution to the civil war, but it was an important step in the right direction.

The Orthodox bishops must have felt that the jointly negotiated settlement on chemical weapons was a first answer to their desperate prayer on July 25 “that peace and the love of brothers may be restored in the Middle East.” You don’t have to believe in the efficacy of prayer to breathe a quiet “Amen” to their petition.

Core beliefs

Theotokos

Theotokos means “God-Bearer” in Greek, referring to the Virgin Mary as mother of God in the Eastern Orthodox tradition.

To Orthodox Christians, Mary is considered the one who gave birth to God. She is not referred to as Christ-Bearer. This suggests that Orthodox Christians consider Christ as both divine and human. Jesus’ humanity is confirmed in his birth from a woman, who is a real historical person. He is also divine because he was born of the Virgin Mary and conceived by the Holy Spirit.

However, Orthodox Christians do not maintain the Catholic beliefs regarding the immaculate conception of Mary and do not specifically speak to Mary’s freedom from original sin. Like Catholic Christians, Orthodox Christians believe that Jesus was born in a virgin birth.

Mysteries

‘Mystery’ is a term used in Orthodoxy to signify a sacrament in Western Christianity.

This number is derived from Italian theologian Peter Lombard (c.1100-1160), who first defined the seven sacraments (or ‘Mysteries’). This number of acts was later adopted by the Orthodox church. The seven Mysteries are Baptism, the Eucharist, Chrismation, Holy Orders, Holy Unction, Marriage, and Penance.

However, Orthodoxy views any action designed to bring us closer to the presence of God and done through the church as having some sacramental value, beyond these seven. As in the Catholic Church, the Mysteries of the faith convey divine grace to those who receive them worthily.

the church as having some sacramental value, beyond these seven. As in the Catholic Church, the Mysteries of the faith convey divine grace to those who receive them worthily.

The seven mysteries and brief explanations are as follows:

- Baptism: Represents unity and devotion to Christ

- The Eucharist: Communion in which the Orthodox unite

- Chrismation: Confirmation

- Holy Orders: Selective and divine priesthood

- Holy Unction: Healing ministry

- Marriage: Eternal Christian marriage

- Penance: Virtue and nobility signified by confession

Example Coverage

“Orthodox Christians retrieve holy cross from icy Istanbul waters” — Jan. 14, 2015, Ayla Jean Yackley, Reuters

More than a dozen swimmers have braced the icy waters of Istanbul’s Golden Horn to take part in one of the world’s oldest polar bear plunges: the ancient Greek Orthodox rite celebrating the Feast of the Epiphany.

After prayers on Epiphany, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, spiritual leader of the world’s 250 million Orthodox Christians, tossed a wooden cross into the brackish waters of the Golden Horn, an estuary that runs along Istanbul’s oldest quarter, to commemorate the baptism of Jesus Christ in the Jordan River and the appearance of the Holy Spirit 2,000 years ago. The event is held here every Jan. 6, and this year it coincided with the coldest winter storm this season. — Read more.

Orthodox Christians Mark Baptism of Jesus at River Jordan

By Peggy Fletcher, Religion News Service

Jan. 1, 2000

(RNS) JORDAN RIVER, Israeli-Occupied West Bank — Garbed in a loose white robe, 38-year-old Anne Maniuk waded into the grimy brown river full of reeds, dunked her head under, and emerged with a great smile on her face and hands lifted heavenward: “In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit,” said the teacher in her native Russian language, her short blond hair tied into a white kerchief, now dripping wet.

At the same time, a nun splashed in the murky water, trailing a heavy long black habit and headdress. Nearby, men sporting long hair and beards, muscles rippling through skimpy T-shirts, swam a few strokes into the center of the river, before returning to shore.

The more timid, or well dressed, meanwhile, crowded the water’s edge to receive a blessing and a splash of droplets from an Orthodox priest, or scoop up a sample of the holy water in a plastic bottle to carry back home.

Every year, Orthodox Christians around the world celebrate the baptism of Jesus on Jan. 18. In some parts of Russia, Christians cut through the ice of frozen streams and rivers, in order to make a ritual dip in commemoration of the date, said Slava Molitvin, a Russian-Israeli tour guide, here with a group of 18 pilgrims. “For us, this water is not so cold,” he said.

Still, a dip in the Jordan River site, revered by many as the actual place of Jesus’ baptism 2,000 years ago, has a special meaning for pilgrims. And on Tuesday (Jan. 18), several thousand Orthodox Christians, gathered here for millennial year celebrations from as far away as Greece, Russia and the Ukraine, came to view the river of the Bible and sample its waters first hand. “I had imagined a big river. I was surprised to see how small. and dirty it was,” confessed Maniuk as she stood on the river bank for nearly two hours in prayerful anticipation, singing hymns and uttering prayers with a group of seven other women friends. “Still, this is the water of Jesus Christ,” so it can’t be really dirty, said the woman, who saved her earnings for two years in order to make the month-long pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

Finally, the signal came. An Orthodox priest descended to the river’s edge, threw a flower-decorated cross into the water while simultaneously releasing a dove into the air. Maniuk and her friends took the plunge. They held hands and sang in the water. They embraced each other. “It was wonderful,” Maniuk said after emerging barefoot and dripping wet a few minutes later.

As far as appearances go, this baptismal site on the Israeli-occupied West Bank side of the Jordan River, has probably known better days. Approaching the river from ancient Jericho, the remains of a enormous monastery courtyard lies in ruins. Here, pilgrims en route to the Jordan must have rested from the heat of the desert under the shade of date palms. The date trees are now dead stumps enabling soldiers from a nearby army post to scan the area which lies along the border with Jordan. Signs warning of minefields are posted along the monastery walls.

At this southernmost point of the Jordan near its outlet to the Dead Sea, the river water today is largely a cesspool of modern agricultural sewage dumped by Israeli kibbutzim far upstream.

Just one set of narrow concrete steps leads down to the water, creating huge human traffic jams on holidays like this one, when Palestinian Christians, Orthodox clergy and foreign tourists all converge at once.

One such visitor is a Russian Orthodox priest, Father Germanos, from the Russian city of Tula, about 200 miles south of Moscow. This is his seventh visit to the site, he said, adding that on his last trip in the fall his finger was healed of rheumatism when he dipped in the water.

“I take the water in bottles back to Russia,” he said. “And this way I bring the holiness of Jesus and the river back to the people there. People use the water to clean their apartments of evil spirits, and they even drink it if they are sick.”

As far as Father Germanos is concerned, there is no doubt in his mind that the place where Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist is right here at this very site.

Many European and American pilgrims, however, prefer to take the dip at the Israeli-developed “Yardenit” pilgrim site about 100 miles further north. There, where the Sea of Galilee flows into the Jordan, the water is considerably cleaner and access is not through a militarized border zone.

Near here, meanwhile, the government of Jordan has recently developed its own baptismal site on its side of the Jordan River, in an area known as Wadi Al Karrar. The site lies alongside a small fresh water spring and an ancient monastery. It is here that Pope John Paul II will visit during his March tour of the Holy Land.

Not to be outdone, however, Israel is planning to upgrade this facility on the West Bank side of the Jordan River. The multimillion dollar improvements will include a better access road to the river, as well as modern amenities such as toilets, say Israeli military administration officials who control the area.

Still, given the proximity to the border, it’s unlikely the minefields surrounding the old monastery will be removed or the military jeeps that circulate here endlessly will give way to easy tourism access. Nor is it likely the water quality of the Jordan River itself will be improved.

For the moment, however, pilgrims like Father Germanos, remain undisturbed by the water’s brown tinge. “I myself have drunk the water on three different occasions,” he said. “In the Bible it says that even if you drink poison and you believe, nothing will happen.”

Celebrations

Overview

Most Christian denominations schedule worship around a liturgical calendar, which includes holy days of celebration to commemorate events in the life of Jesus Christ or the saints.

The degree to which these events are celebrated varies greatly with the denomination. Catholic and Orthodox denominations are more likely to commemorate the lives of the saints than Protestants.

The major holidays and observances in Christianity are Lent, Good Friday, Easter, Pentecost, Advent and Christmas.

Religion journalists generally cover these in some way, whether through enterprise stories, photography or daily coverage of events.

Example Coverage

“Orthodox Christmas melds Yup’ik and religious traditions” — Jan. 8, 2015, Lisa Demer, The Alaska Dispatch

NAPASKIAK — Under delicate snowflakes crocheted by the town mayor, beneath a grand chandelier imported from Russia, a Yup’ik priest in a remote Southwest Alaska village led parishioners in song, prayer and praise day and night this week for Orthodox Christmas, or Slaviq.

Most of America took down Christmas trees a week ago, but here in the heart of Orthodox Christian Alaska, people were cutting fresh trees for the holy holiday’s pinnacle on Wednesday, Orthodox Christmas Day. The celebration will stretch on for a week or more. — Read more.

April Fool’s isn’t a religious holiday, but there are some religious roots

By Peggy Fletcher, Religion News Service

March 31, 2014

(RNS) Let’s be clear: April Fools’ Day is not a religious holiday.

It does, however, trace its origins to a pope.

The day began, most believe, in 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII decreed the adoption of the “Gregorian calendar” — named after himself — which moved New Year’s Day from the end of March to Jan. 1.

The change was published widely, explains Ginger Smoak, an expert in medieval history at the University of Utah, but those who didn’t get the message and continued to celebrate on April 1 “were ridiculed and, because they were seen as foolish, called April Fools.”

Even though the annual panoply of pranks meant to mock the gullible or to send a friend on a “fool’s errand” may not be grounded in any ancient religious merrymaking, the notion of “holy fools” does have a long and respected place in Judeo-Christian history.

Hebrew prophets were often scorned as mad or eccentric for pronouncing unwelcome or uncomfortable truths. The Apostle Paul talked to the Corinthians about becoming “fools for Christ.” And Eastern Orthodoxy still sees the “holy fool” as a type of Christian martyr.

Such views are wrapped up in paradox.

“If the wisdom of the world is folly to God, and God’s own foolishness is the only true wisdom,” argues British clergyman John Saward in “Perfect Fools: Folly for Christ’s Sake in Catholic and Orthodox Spirituality,” “it follows that the worldly wise, to become truly wise, must become foolish and renounce their worldly wisdom.”

Such role reversals were common during medieval Christian festivals.

Some argue that April Fools’ Day is a remnant of early “renewal festivals,” which typically marked the end of winter and the start of spring.

These festivals, according to the Museum of Hoaxes, typically involved “ritualized forms of mayhem and misrule.”

Participants donned disguises, played tricks on friends as well as strangers, and inverted the social order.

“Servants might get to order around masters, or children challenge the authority of parents and teachers,” the museum’s website notes. “However, the disorder is always bounded within a strict time frame, and tensions are defused with laughter and comedy. The social order is symbolically challenged, but then restored, reaffirming the stability of the society, just as the cold months of winter temporarily challenge biological life, and yet the cycle of life continues, returning with the spring.”

Some have mistaken these celebrations for medieval Christianity’s Feast of Fools, which took place each January.

For centuries, this feast was seen as “a disorderly, even transgressive Christian festival, in which reveling clergy elected a burlesque Lord of Misrule, who presided over the divine office wearing animal masks or women’s clothes, sang obscene songs, swung censers that gave off foul-smelling smoke, played dice at the altar, and otherwise parodied the liturgy of the church,” says historian Max Harris, author of “Sacred Folly: A New History of the Feast of Fools.” Afterward, revelers would “take to the streets, howling, issuing mock indulgences, hurling manure at bystanders, and staging scurrilous plays.”

But that’s not what happened, he says.

Even Victor Hugo’s famous novel “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame” — and the Disney animated film loosely based on it — got it wrong. In Hugo’s opening passages, Harris explains, the novelist describes “rowdy theatricals and underworld parades of lay Parisians … ‘on the sixth of January 1482’ as a combined celebration … of the day of the kings and the Feast of Fools.”

Those two celebrations were “nothing of the sort,” Harris wrote in an email from his home in Wisconsin. “Indeed, they were not even an accurate portrayal of lay festivities.”

Such revelry, Harris says, “was almost wholly a figment of Hugo’s imagination.”

So what was it really like?

The actual feast was developed in the late 12th and early 13th centuries as “an elaborate and orderly liturgy for the day of the Circumcision (Jan. 1),” Harris says, “serving as a dignified alternative to rowdy secular New Year festivities.”

The goal, he emphasizes, was “not mockery but thanksgiving for the incarnation of Christ.”

Role reversals did occur, but their point, Harris said, was to underscore Mary’s joyous affirmation that God “has put down the mighty from their seat and exalted the humble.”

The “fools” represented those chosen by God for their lowly status.

This liturgical feast was largely confined to cathedrals and collegiate churches in northern France.

Centuries later, high-ranking clergy “who relied on rumor rather than firsthand knowledge, attacked and eventually suppressed the feast,” Harris saidl. “Eighteenth- and 19th-century historians repeatedly misread records of the feast; their erroneous accounts formed a shaky foundation for subsequent understanding of the medieval ritual.”

The Feast of Fools was finally forbidden by the Council of Basle in 1435.

That misunderstanding of history, though, eventually found its way into Hugo’s novel and even the Catholic Encyclopedia, which linked the “feast of fools” to the pagan celebration of Saturnalia, whose “parody must always have trembled on the brink of burlesque, if not of the profane.”

That is unfortunate, said Harris, who has read and studied the original documents from the time. In his mind, the feast was more sanctified than sacrilegious.

Scripture

Overview

Although there are numerous scriptures used by Christians, the Bible, including 39 books from the Old Testament and 27 books from the New Testament, is the central religious text.

The Old Testament consists of Hebrew Scripture about the covenant God had with Israel. The New Testament forms the basis of Christian faith and recounts the life and teachings of Jesus Christ.

Eastern Orthodox Christians include most parts of the Apocrypha in the biblical canon. (The Apocrypha, from the Greek word that means “things hidden,” is made up of religious writings included in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament, but not the Hebrew Bible.

Orthodox Christians and Roman Catholics accept them as divinely inspired, but Protestants do not.) The Greek Orthodox Church collaborated on the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, published by the National Council of Churches USA, which includes the Apocrypha.

However, the Eastern Orthodox canon includes different Apocrypha books than either Protestants or Roman Catholics do. The variations are based on which books were present in the Septuagint and its early manuscripts.

(The Orthodox omit 2 Esdras from the Protestant Apocryphal but add 3 and 4 Maccabees and Psalm 151.)

-

“A Dictionary of Orthodox Terminology”

Fotios K. Litsas of the University of Illinois at Chicago maintains an online dictionary of terms associated with Orthodox Christianity.

Example Coverage

“Jackson’s Orthodox Church built on ‘zeal and eagerness’” — Jan. 31, 2015, Nathan Handley, The Jackson Sun

St. Nicholas Orthodox Church in Jackson held its first meeting in 2011, but it didn’t get its first, full-time priest until this year.

Father Matthew Snowden has been serving less than a month, but Laura Wilson, one of the church’s founding members, said there is already a great difference. Wilson said the priest is a very important part of the services.

The church previously had a priest visit to conduct services a few times a month from St. John’s Orthodox Church in Memphis. — Read more.

Drag queen winner of Eurovision contest condemned by Russian Orthodox Church

By Sophia Kishkovsky, Religion News Service

May 12, 2014

MOSCOW (RNS) A spokesman for the Russian Orthodox Church strongly denounced the Eurovision Song Contest’s selection of a drag queen as its winner, saying it was a sign of the world’s moral decline and part of an effort to “reinforce new cultural norms.”

Conchita Wurst, the stage name of a former band singer from Austria named Tom Neuwirth, won the 59th installment of the competition, held this year in Copenhagen, with a song titled “Rise Like a Phoenix,” which she performed early Sunday (May 11) as a bearded woman in a form-fitting gold dress.

The Eurovision contest draws well over 100 million viewers annually, and the contest has become a point of national pride in Russia, which began competing in the 1990s.

“The process of the legalization of that to which the Bible refers to as nothing less than an abomination is already long not news in the contemporary world,” Vladimir Legoyda, chairman of the church’s information department, told the Interfax news agency. “Unfortunately, the legal and cultural spheres are moving in a parallel direction, to which the results of this competition bear witness.”

Legoyda said the result of the competition was “yet one more step in the rejection of the Christian identity of European culture.”

On Monday (May 12), Vitaly Milonov, a municipal legislator in St. Petersburg known for his anti-gay activism, appealed to Russia’s culture ministry to ban any future performances in Russia by Wurst.

Other Russian commentators pointed out that Russia’s pop-music scene is known for flamboyant performers who bend gender lines.

Both the Kremlin and the Moscow Patriarchate have been positioning Russia as a moral bastion in contrast to Europe and the United States.

The Moscow Patriarchate has condemned the legalization of same-sex marriage in European countries and defended anti-gay legislation in Russia, saying it is meant to protect minors.

Last June, speaking at a monastery atop Mount Athos in Greece, Patriarch Kirill I, the primate of the Russian Orthodox Church, warned that moral relativity is “that ground on which only the Antichrist can come” and singled out sexual morality as a sign of relativism.

“We see what is happening today,” he said. “Same-sex marriages, euthanasia, abortion — that which was always regarded as evil from the point of view of divine truth is no longer considered evil.”

Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Russian church’s Department of External Church Relations, said at a conference in Moscow in December that the West was destroying marriage as “the God-created union of man and woman” and warned that countries that are drawn into Europe’s orbit would be forced to accept alien values, in a clear reference to Ukraine.

In April, a controversial group of Russian Orthodox youth activists raided the screening of a documentary film about LGBT teenagers, who are often driven to suicide by their sense of isolation in Russia.

Notes on coverage

General guidelines

- Take care with labels. Christianity is diverse, and beliefs can vary greatly within denominations. Ask questions about beliefs before leaping to assumptions.

- Learn the correct terms. Many Christian denominations come with their own terms and titles for the structure or hierarchy of leadership within that denomination. Some congregations are governed independently within national guidelines and others embrace a strict hierarchy. Learn the correct titles and don’t try to generalize across denominations.

- Consider stories on the major Christian holidays, Lent, Good Friday, Easter, Pentecost, Advent and Christmas.

- Orthodox denominations are rarely a source of breaking news, but journalists may be interested in their growing numbers. Together, Orthodox churches account for many more members than some Protestant denominations that receive much more news coverage.

- The Eastern Orthodox follow the Julian Calendar instead of the Gregorian Calendar used by Western churches. Christmas falls on Jan. 7, and the date of Easter differs each year.

- Priests may be married in Eastern Orthodox traditions if they marry before ordination, but monks and bishops must be single.

- The Oriental Orthodox Churches churches split from the Eastern Orthodox churches in 451 A.D. because they rejected the Christological definition of the 4th Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon, which asserted that Christ is one person in two natures, fully human and fully divine — a definition that the Eastern Orthodox Churches accepted. The Oriental Orthodox Churches include the Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopian, Syrian, Malankara and Eritrean churches.

Example Coverage

When obedience is next to Godliness

By Laura Turner, Religion News Service

April 20, 2007

Struggling to train an unruly dog in your jam-packed life and think you’ve exhausted all resources?

Maybe it’s time to take a deep breath and start acting like a monk.

For nearly 40 years, an order of Eastern Orthodox monks at the New Skete Monastery in Cambridge, N.Y., have funded their monastic lives by training the most stubborn of misbehaving dogs for thousands of frustrated families. The training benefits the pups, the families and maybe most of all the monks, who say the discipline and focus required for obedience training puts them in a deeper spiritual place.

“Working with dogs has put us in touch with the mystery of God and nature,” said Brother Christopher, the program’s director. In keeping with their monsatic practice the New Skete monks do not use last names.

The monks have trained thousands of dogs in their three-to-four week programs, which costs $1,300, including canine room-and-board. After the training period is over, the monks convey to owners how important it is to continue developing the relationship and training outside the monastery.

The monks are the subject of a new show on Animal Planet called “Divine Canine: With the Monks of New Skete.” It’s an 11-part series, airing Mondays from 8 to 8:30 p.m. ET, that examines life at the monastery in terms of “loyalty, faith, discipline and dogs.”

Too often, people look at religion and spirituality in narrow and structured ways, said Brother Christopher, who has been training dogs for 25 years. As a result, they don’t realize the powerful spiritual feelings that often stem from everyday tasks like dog training. Ditching their robes for jeans and sweaters for part of each day, the monks find their interactions with man’s best friend to be a heavenly outlet.

“Many people think of their religion when they pray at the beginning and end of the day, as a more formal religious aspect of our lives,” said Brother Christopher. “As monks, we’re very aware of the whole of life being contemplative in character.”

In the serenity of their 500-acre monastery nestled in Cambridge’s rolling hills, the monks say they employ a holistic approach that brings spiritual gains and improves the behavior of the canines.

“What’s so important in the life of a dog is the relationship with their owner,” Brother Christopher said. “Rather than going about training in a mechanical way, we try to help people understand that the training has to serve the relationship for both to allow it to blossom.”

The first episode of the TV series shows the successful training of a pampered dog named Stella, whose owners admitted they couldn’t control. They dressed her in sweaters and strolled her around in a baby stroller rather than making her walk. Stella often paid her owners no mind when they voiced even simple commands. After four weeks with Brother Christopher, Stella went home as cute as she came in, but also with respect for her owners.

“We want owners to realize the potential that caring and training for a dog can have for both you and your dog,” said Brother Christopher. “It can be a total enrichment.”

Aside from training unruly dogs for customers, the monks also care for and breed world-class German shepherd puppies. The experience of dog training has added a truly happy element to the intense spiritual contemplation of the monks’ daily routines.

“If dogs were not here, we’d probably be a group of somber, bitter old men,” Brother John said on the TV show.

International sources

Asia

-

Korean Orthodox Church

Includes a historical background of Orthodoxy in Korea as well as links and contact information on The Orthodox Metropolis of Korea and its parishes.

-

Orthodoxy in China: Orthodox Fellowship of All Saints of China

Offers news and information and historical information on Orthodoxy practice in China.

-

Pravoslavie Orthodox Web Portal

Current news and events. Articles’ sections: religion, history, theology, culture, politics.

-

Ukrainian Orthodox Church

Autonomous Church of Eastern Orthodoxy in Ukraine, under the ecclesiastic jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Canada

-

Heather J. Coleman

Coleman is an associate professor of history and classics at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. She studies religion in Russia. Her current research is based on a book project, “Holy Kyiv: Priests, Communities, and Nationality in Imperial Russia, 1800-1917,” which explores the ethno-religious diversity of Kyiv diocese its relationship with the pastoral mission of the Orthodox clergy there. She also has expertise on Russian Baptist history and theology.

-

Douglas John Hall

Douglas John Hall is author of The Cross in Our Context: Jesus and the Suffering World, in which he examines whether Christianity teaches some a love of consumption and waste. He is emeritus professor of theology at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec. He has written extensively about neo-Orthodoxy.

-

Myroslaw Tataryn

Professor of Religious Studies and Theology at St. Jerome’s University at the University of Waterloo. His primary focus in systematic theology among the Orthodox in particular. His dissertation studied the Orthodox Theologians at l’Institute Saint Serge, Paris (1925-1939) and their perception of St. Augustine’s Theology.

-

Lucian Turcescu

Professor and Chair of Theological Studies at Concordia University in Montreal. His research focuses on early Christianity and on the relationship between religion and politics.

Europe

-

Ecumenical Patriarchate Holy Metropolis of Italy and Malta

The Sacred Church of Saint Jacob, Apostle Greek Orthodox Parish of Florence. This is an Orthodox Church in the city center of Florence, Italy. The website gives access to links and materials regarding Orthodoxy in the region and other Orthodox sites. Contact through the website.

-

In Communion: Website of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship

The Orthodox Peace Fellowship website. The Fellowship, located in The Netherlands, does theological research, publishing, and assistance in conflict areas regarding peacemaking.

-

Russian Orthodox Church in Belgium and the Netherlands

A website about the Russian Orthodox Diocese in Belgium and the Diocese in the Netherlands. Also includes information about the Archbishop of Brussels and Belgium.

-

The British Orthodox Church within the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate

This is the website of The British Orthodox Church, which is canonically part of the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria.

-

The Ecumenical Council of Churches in the Czech Republic

ECC is an association of churches in the Czechoslovakia region. The Orthodox Church in the Czech Lands is a part of this association. The media contact for the World Council of Churches is Marianne Ejdersten.

The Middle East

-

Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, Russian Orthodox Church Abroad

Includes history of the mission and detailed information on monastic communities in the Holy Land.

-

Synod of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem

The official website of Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Information on the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, news, publications, and interviews.

U.S. sources & resources

Major organizations

-

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

The Greek Orthodox Archdioceses of America is the largest Orthodox denomination in America,with about 1.5 million members.

-

National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA

The National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA is an umbrella organization of Protestant, Anglican, Orthodox, historic African American and Living Peace denominations. The NCCC frequently files amicus briefs in religious and civil liberties cases. Philip E. Jenks is press contact.

-

Orthodox Church in America

The Orthodox Church in America website gives a detailed explanation of the faith. It also lists the 19 self-governing and self-ruling Orthodox churches worldwide, which include the OCA. (The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America is directly under the authority of the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople in Turkey, and is not administratively related to the Church of Greece.) Primate of the Orthodox Church in America (historically Russian) is Metropolitan Tikhon, located in Syosset, N.Y. Find local parishes.

-

Standing Conference of the Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas (SCOBA)

This organization brings together the canonical hierarchs of the Orthodox jurisdictions in America. The purpose of the conference is to make the ties of unity among the canonical Orthodox churches and their administrations stronger and more visible.

U.S. resources

-

Orthodox Christian Information Center

The site is an online article repository, with over 850 articles and 3,000 printed pages on Orthodox Christianity. It posts information for members and nonmembers.

-

Orthodox Church in America Directories

Includes Orthodox dioceses, parish listings, clergy listings, monastic community listings, military chaplain listings, organizations, seminaries, churches in North America, and world Orthodox churches.

-

Orthodoxy in America

An online directory of the Orthodox Church in North America, specifically of the parishes, monasteries, and seminaries of the twelve major Orthodox jurisdictions in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

-

Standing Conference of the Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas (SCOBA)

This organization brings together the canonical hierarchs of the Orthodox jurisdictions in America. The purpose of the conference is to make the ties of unity among the canonical Orthodox churches and their administrations stronger and more visible.

-

Association of Religion Data Archives

The Association of Religion Data Archives provides numerous data collections on religion.

-

Orthodox Christian Education Commission

The Orthodox Christian Education Commission is an agency of the Standing Conference of the Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas and was founded as a forum to exchange ideas and search for solutions to education problems.

-

The Orthodox Theological Society in America

The society was organized under the auspices of the Standing Conference of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas to promote Orthodox theology, cultivate fellowship and cooperation among Orthodox Christians and coordinate the work of Orthodox theologians in the Americas. Email through the website.

-

Orthodox Peace Fellowship

The Orthodox Peace Fellowship is an international association of Orthodox Christians, located in the Netherlands, who study and advocate on issues of peace and conflict in local, national and international contexts.

-

Orthodox Fellowship of the Transfiguration

The Orthodox Fellowship of the Transfiguration a pan-Orthodox association that addresses environmental issues.

-

International Orthodox Christian Charities

International Orthodox Christian Charities has provided humanitarian assistance through some of the most troubled decades in recent history. Specifically, it is the international humanitarian organization of the Standing Conference of Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas. It is based in Baltimore and has programs in several African countries.

-

Beliefnet.com: Christian Orthodox

A page on Eastern Orthodox churches and basic information on Orthodox faith.

-

Orthodox Christian Mission Center

The Orthodox Christian Mission Center focuses on evangelism. OCMC’s mission is to make disciples of all nations by bringing people to Christ and His Church.

-

Orthodox Christian Fellowship

The Orthodox Christian Fellowship is the official campus ministry effort under the Standing Conference of the Canonical Orthodox Bishops in the Americas. It is a pan-Orthodox effort, overseen by an executive committee and aided by an 11-person student advisory board.

-

Orthodox Christian Prison Ministry

The Orthodox Christian Prison Ministry ministers to men and women behind bars.

-

Orthodox Christian Association of Medicine, Psychology and Religion

The Orthodox Christian Association of Medicine, Psychology and Religion exists to foster interdisciplinary dialogue and promote Christian fellowship among professionals in medicine, psychology, and religion. Members pursue an understanding of the whole person that integrates the basic assumptions of medicine, psychology, and religion with the Orthodox Christian faith in educating and serving church and community. Demetra Velisarios Jaquet is president.

-

Fordham University Orthodox Christian Studies

Fordham University in New York offers this program of study. The mission of their Orthodox Christian Studies Center is to provide a venue for the academic study of Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

Articles

-

“More Protestants Find a Home in the Orthodox Antioch Church”

Read an Oct. 2, 2009 New York Times story on the lure of an Orthodox church for Protestant Christians.

-

“Bartholomew I, Christian Orthodox leader, to convene environmental meeting in New Orleans”

Read a Sept. 23, 2009, New Orleans Times-Picayune story on Bartholomew’s visit to the United States and the Religion, Science and the Environment Symposium.

-

“Bring on the Feast: For Greek Easter, a Month of Prep”

Read an April 8, 2009, Washington Post feature on the complex preparations for a Greek Easter feast.

-

“Soul of Russia: Driven underground for 75 years, the faith of the Russian tsars now enjoys favored status”

Read an April 2009 National Geographic story on the new Russian Orthodox Church rising after the fall of the Soviet Union.

-

“Russian Leaders Attend Installation of Orthodox Patriarch”

Read a Feb. 1, 2009, New York Times story on the installation of a new patriarch for the Russian Orthodox Church. He was the first patriarch elected since the fall of the Soviet Union.

-

“An Eye for Glory”

Read an October 2002 Dallas Morning News profile of an Orthodox Christian icon painter.

-

“New Religious Movements: An Orthodox Perspective”

“New Religious Movements: An Orthodox Perspective” is an article written by Vladimir Fedorov on World Council of Churches site in 1998.

National sources

-

Emmanuel Clapsis

Emmanuel Clapsis is professor of dogmatic theology at Hellenic College and Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline, Mass. Among his publications is The Orthodox Churches in a Pluralistic World: An Ecumenical Conversation.

-

John H. Erickson

John H. Erickson is professor of church history at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in Crestwood, N.Y.

-

Donald M. Fairbairn

Donald M. Fairbairn Jr. is professor of historical theology at Evangelical Theology Faculty in Leuven, Belgium. Previously he was a professor of historical theology and missions at Erskine Theological Seminary in Due West, S.C. He is the author of Eastern Orthodoxy Through Western Eyes.

-

Thomas E. FitzGerald

Thomas E. FitzGerald is professor of church history and historical theology at Hellenic College and Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline, Mass.

-

Veselin Kesich

Veselin Kesich is professor emeritus of the New Testament at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in Crestwood, N.Y.

-

John Anthony McGuckin

John Anthony McGuckin is a professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He is the author of The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Its History, Doctrine and Spiritual Culture (2008) and many other books and articles.

-

Jerry Pankhurst

Jerry G. Pankhurst is a sociology professor at Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio. He is co-editor of Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the Twenty-First Century.

-

Aristotle Papanikolaou

Aristotle Papanikolaou is Archbishop Demetrios Professor of Orthodox Theology and Culture and

Senior Fellow and co-founder of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center at Fordham University in the Bronx, N.Y. -

Elizabeth H. Prodromou

Elizabeth Prodromou is Senior Scholar in the International Studies Program at Boston College. She is also non-resident Senior Fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center. She served on the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) from 2004-2012, and is a Co-President of Religions for Peace.

Regional sources

NORTHEAST

-

Peter C. Bouteneff

Peter C. Bouteneff is a professor of systematic theology at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary in Yonkers, N.Y. He is interested in popular culture and has worked for the World Council of Churches. He wrote the article “All Creation in United Thanksgiving: Gregory of Nyssa and the Wesleys on Salvation” in the book Orthodox and Wesleyan Spirituality.

-

George Dion Dragas

George Dion Dragas is professor of patrology/patristics at Hellenic College and Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline, Mass.

-

Michael Plekon

Michael Plekon is professor of religion and culture at City University of New York in New York City. He wrote a chapter titled “The Russian Religious Revival and Its Theological Legacy” in The Cambridge Companion to Orthodox Christian Theology (2008).

-

Theodore Stylianopoulos

Theodore Stylianopoulos is professor of Orthodox theology and the New Testament at Hellenic College and Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline, Mass.

SOUTH

-

Frank S. Alexander

Frank S. Alexander is a professor and founding director of the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University in Atlanta. He is co-editor of The Teachings of Modern Orthodox Christianity on Law, Politics & Human Nature (2007). He is an expert on homelessness and housing policy.

-

Ted A. Campbell

Ted A. Campbell is an associate professor of church history at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. He is the author of The Gospel in Christian Traditions (2008).

-

Phillip Charles Lucas

Phillip Charles Lucas is a professor of religious studies at Stetson University in DeLand, Fla. He is the co-editor of Cassadaga: The South’s Oldest Spiritualist Community (University Press of Florida, 2000) and general editor of Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. His other publications include “Enfants Terribles: The Challenge of Sectarian Converts to Ethnic Orthodox Churches in the United States,” published in Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions (2003).

-

John Witte Jr.

John Witte Jr. directs the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory University, where he also teaches law. He is an expert on legal issues related to marriage, family, Christianity and religious freedom. His books include Church, State and Family: Reconciling Traditional Teachings and Modern Liberties and Religion and the American Constitutional Experiment.

IN THE MIDWEST

-

Paul L. Gavrilyuk

Paul L. Gavrilyuk is an associate professor in theology at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. His publications include “Eastern Orthodoxy,” The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion (2007).

-

Alexander G. Golitzin

Alexander G. Golitzin is a theology professor at Marquette University in Milwaukee. He is an author of the Historical Dictionary of the Orthodox Church.

-

Robert L. Nichols

Robert L. Nichols is a professor emeritus in history at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn. He is co-editor of Russian Orthodoxy Under the Old Regime.

IN THE WEST

-

Stephen K. Batalden

Stephen K. Batalden is a history professor at Arizona State University in Tempe. He is the editor of Seeking God: The Recovery of Religious Identity in Orthodox Russia, Ukraine and Georgia.

-

Eugene J. Clay

Eugene J. Clay is an associate professor in religious studies at Arizona State University in Tempe. His publications include “Russian Orthodoxy,” published in Religion and American Cultures: An Encyclopedia of Traditions, Diversity and Popular Expressions.

-

Alexei D. Krindatch

Alexei D. Krindatch is director for membership growth and research at the Patriarch Athenagoras Orthodox Institute at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, Calif., and a leading researcher on Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The institute is “inter-Orthodox” and describes itself as an independent, not-for-profit teaching and research institution affiliated with the GTU and the University of California.

-

Richard G. Hovannisian

Richard G. Hovannisian is a professor emeritus in history at University of California, Los Angeles. He has written about and studied the history of Orthodox Christianity.

Sources by branch

THE GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH

-

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

The Greek Orthodox Archdioceses of America is the largest Orthodox denomination in America,with about 1.5 million members.

-

The Greek Orthodox Church

The website of the Greek Orthodox Church. Is a resource for relevant texts, monasteries, churches, seminaries, and other relevant resources related to the church.

-

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America: For the Media

The site provides a summary of the faith for reporters.

-

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America: Monastic Communities

Several monasteries are scattered across the country. See a list with their contact information.

-

Archdiocesan Hellenic Cultural Center

The Hellenic Cultural Center of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America was established in 1986 with the goal of cultivating the Orthodox heritage and Hellenic customs, culture and traditions within the Greek-American community.

-

Greek Orthodox Chaplains

Greek Orthodox chaplains serve full-time as chaplains in the armed forces; others have assumed additional responsibilities as chaplains at Veterans Administration hospitals, with local police forces, at prisons and in hospitals.

-

Archdiocesan Cathedral of the Holy Trinity

The Cathedral of the Holy Trinity has been serving Greek Orthodox Christians for more than a century. The cathedral provides regular worship, counseling, Christian education, human services and cultural programs for people in the New York City area.

-

Hellenic College Holy Cross

Hellenic College Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology provides undergraduate and graduate education. Hellenic College Holy Cross is on a 52-acre campus in Brookline, Massachusetts.

-

St. Basil Academy

St. Basil Academy is the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese home away from home for children in need. The academy is in Garrison, N.Y.

-

St. Photios National Shrine

The St. Photios National Shrine is the only Greek Orthodox National Shrine in the country. It is primarily a religious institution and is located in America’s oldest city, St. Augustine, Florida.

-

Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America: Parish Directory

The website of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America also provides a parish directory that allows surfers to search by city, state and ZIP code.

RUSSIAN ORTHODOX

-

The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia

This is the website for the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, which is an arm of the Russian Orthodox Church. Includes news, dioceses, history, and other information on the church.

-

The Russian Orthodox Church in America

This site gives a history and summary of the Russian Orthodox Church in the United States and lists parishes nationwide.

-

St. Innocent Orthodox Theological Seminary

The seminary was founded in 1976. Its name and location have changed through the years; since 2006 it has been in Roswell, N.M.

-

Orthodox Voices Blog

This site has news and information about the Russian Orthodox Church, specifically the Russian Orthodox Church in America. The content is about Christianity in general, faiths outside Orthodoxy, and Orthodoxy.

-

Religious Books for Russia

Religious Books for Russia was founded in 1979 to provide religious books for Orthodox Christians in the Soviet Union. Since it is now possible to publish and distribute religious literature in Russia, the organization, which is based in LaGrangeville, N.Y., assists with the publication in Russia of the best contemporary Orthodox theological and educational materials. Books are distributed free throughout Russia.

AMERICAN ORTHODOX

-

Orthodox Church in America

The Orthodox Church in America website gives a detailed explanation of the faith. It also lists the 19 self-governing and self-ruling Orthodox churches worldwide, which include the OCA. (The Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America is directly under the authority of the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople in Turkey, and is not administratively related to the Church of Greece.) Primate of the Orthodox Church in America (historically Russian) is Metropolitan Tikhon, located in Syosset, N.Y. Find local parishes.

-

Department of Military Chaplaincies

It supports the ministry of Orthodox military chaplains who, while serving as full-time priests and noncombatant full-time military officers, celebrate Orthodox liturgical services and the Holy Mysteries; offer counseling on all levels; visit hospitals, units, barracks, flight lines and ships; attend command-level briefings; and advise commanders on religious, moral and social issues. Contact the Very Rev. Theodore Boback, executive director.

-

OCA Board of Theological Education

The Board of Theological Education establishes, maintains and oversees the general standards and curriculum for the education and formation of clergy in the Orthodox Church in America’s three seminaries.

-

OCA Office of Communications

Produces and distributes official statements and news releases of the Orthodox Church in America, maintains relations with the media, responds to requests for information of a general and specific nature, and oversees the content and functioning of the Orthodox Church in America’s website.

-

OCA Department of Youth, Young Adult and Campus Ministry

The OCA Department of Youth Young Adult and Campus Ministry produces and distributes official statements and news releases of the Orthodox Church in America, maintains relations with the media, responds to requests for information of a general and specific nature, and oversees the content and functioning of the Orthodox Church in America’s website.

Related source guides

-

Eastern Orthodox churches in the spotlight

-

29 story ideas for Lent, Easter and Passover

-

The transformation of American funerals

-

Reporting on the U.S. Religious Landscape Survey

-

Fallout: the pope and Islam